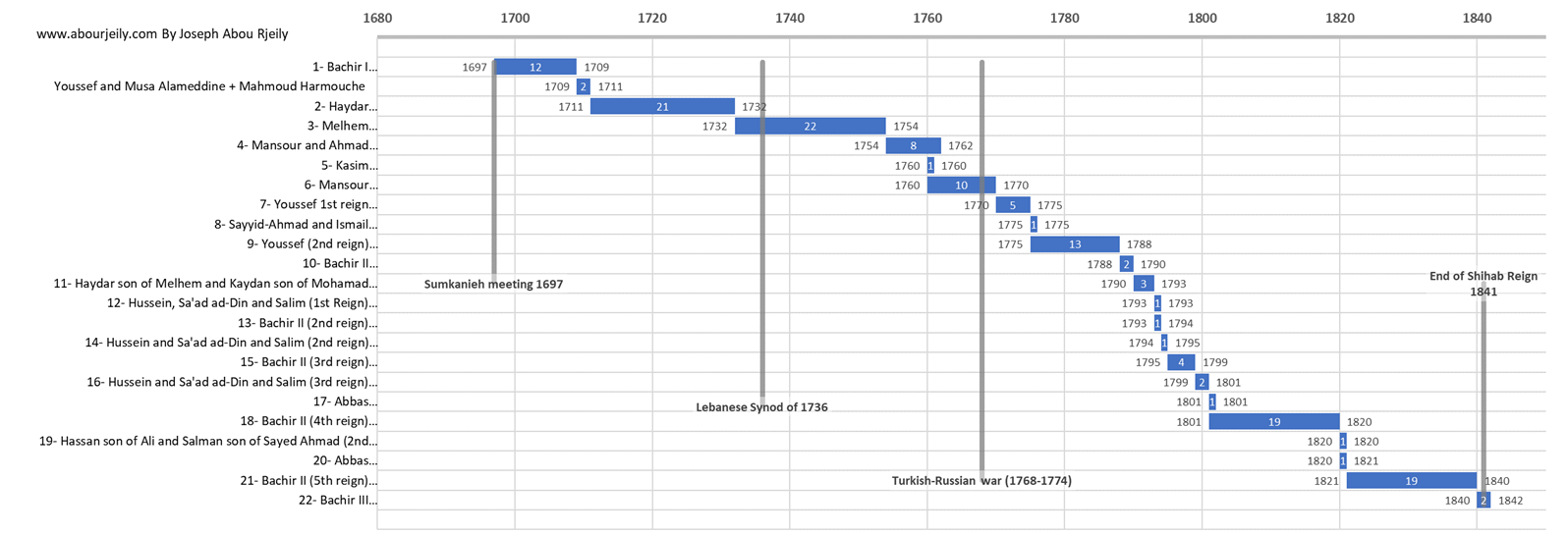

Bachir 2 Shihab Reign

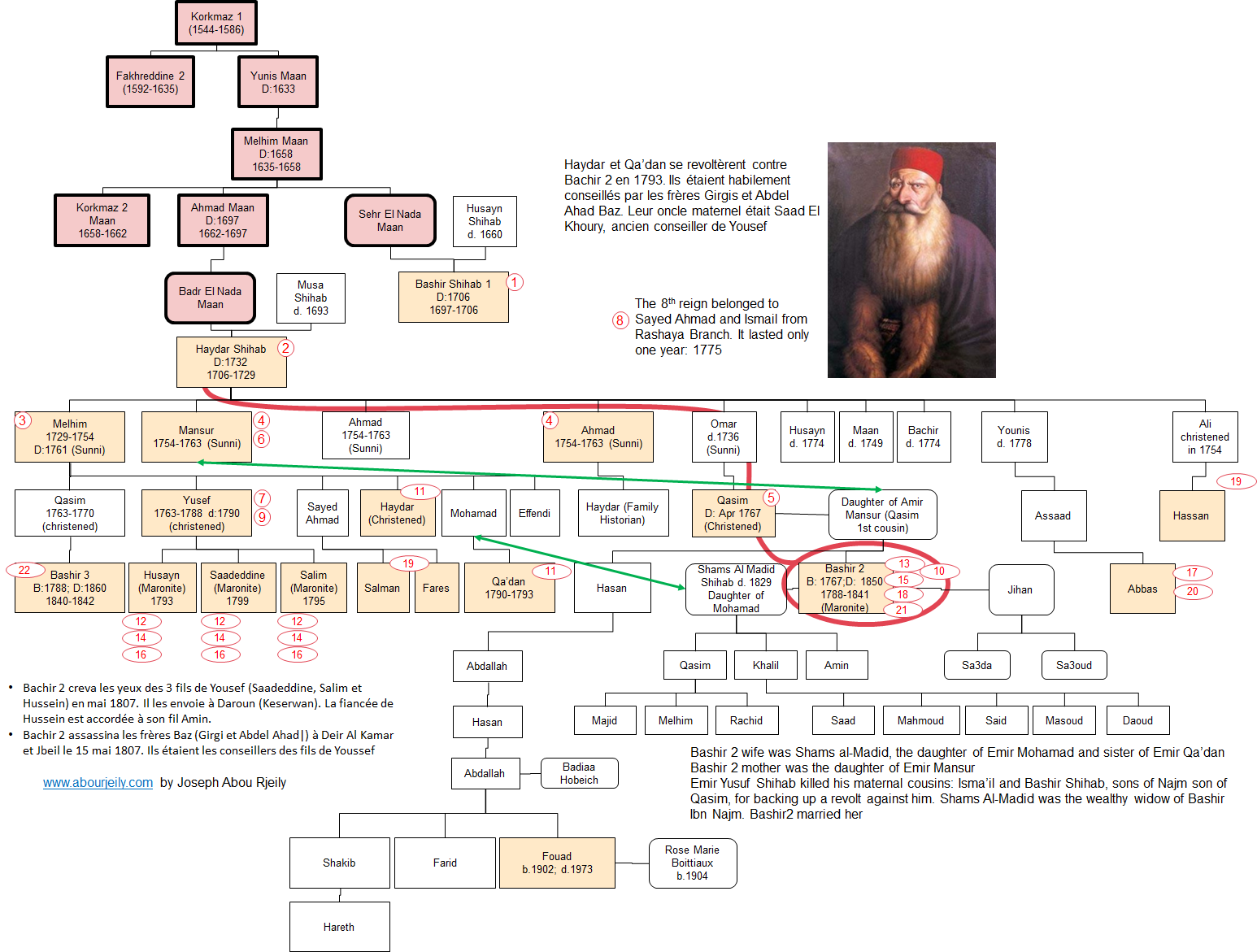

Figure 1: Shihab Chehab Dynasty Family

Le secret du grand émir Bachir 2

La légende montagnarde raconte qu’un jour,

deux paysans, un maronite et un druze, prirent la route à travers le Liban pour

porter leur récolte à l’émir Bachir le Grand qui régnait sur leur pays. Chemin

faisant, les deux compères se disputèrent au sujet de la religion du maitre de

la Montagne. Ne pouvant se départager, ils convinrent d’aller demander à son

premier secrétaire ce qu’il en est en vérité. Pour seule réponse, les deux

montagnards se vinrent administrer deux cents coups de bâton sur la plante des

pieds et furent prévenus qu’on les pendrait à la porte de leur maison s’ils

avisaient de débattre à nouveau de la religion du Grand émir. En somme, dans le

Liban des années 1830, le religieux et le politique devaient demeurer séparés,

par la force si nécessaire.

Voilà qui a de quoi étonner au vu du

système confessionnaliste actuellement en vigueur au Liban. En effet, la vie

politique du pays est aujourd’hui soumise à un subtil équilibre censé garantir

à chaque communauté religieuse sa part au pouvoir. A chaque élection, à chaque

nomination, la religion est déterminante. Le confessionnalisme est partie

intégrante de la vie politique libanaise. Profondément ancré dans l’inconscient

collectif, on en oublie parfois ses origines historiques, comme s’il avait

toujours été et devait toujours être. Toutefois, il fut un temps où les

croyances des maîtres de la Montagne étaient gardées secrètes. Un temps ou les

Libanais se définissaient avant tout par leur rang et non par leur foi

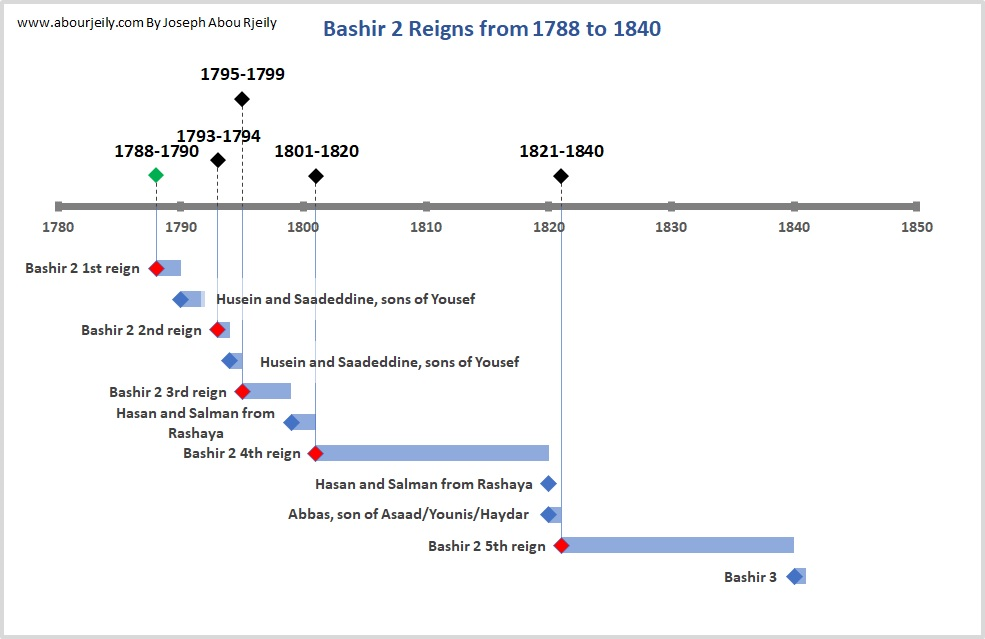

Bachir 2 (2 January 1767–1850) was born in Ghazir, a village in the Keserwan region of Mount Lebanon. He son of Qasim/Omar/Haydar. He reigned 5 times between 1789 and 1840. His father, Qasim converted to Christianity (maronite) prior to his birth. Bashir was among the first members of his extended family to be born a Christian. He was buried in the Armenian patriarchate in Turkey.

Figure 2: Bachir Bashir 2 Shihab

Chehab

Figure 3: Bachir Bashir Chehab Shihab 2

In 1768, when Bashir was still an infant, his father Qasim (قاسم) died. Bashir's mother remarried, and he and his elder brother Hasan were entrusted to the care of tutors and nannies. The children were raised in poverty and did not benefit from the privileges of a princely birth; their branch of the family was relatively poor. Bashir and Hasan developed feelings of mistrust from their childhoods that made them weary of their companions and of members of their own family. Leadership of Qasim's branch of the family was taken up by Hasan. The latter had a reputation for being cruel and aloof.

Bashir, meanwhile, grew to become a cunning, stubborn and clever opportunist who was more able to control his temper and conceal his callousness. He sought out wealth working with his cousin Emir Yusuf in Deir al-Qamar, the virtual capital of Mount Lebanon, where he also gained an education. Bashir's personal qualities established him as a leading figure in the Shihabi court where he engaged in political intrigues. His activity in Deir al-Qamar attracted the attention of Qasim Jumblatt (قاسم جنبلاط), Yusuf's main adversary, who sought to install Bashir at the head of the Emirate. When probed on the subject by the Jumblatt sheikhs, Bashir was noncommittal but left room for negotiations; his hesitance was a result of his financial destitution.

Bashir II's financial fortunes changed in 1787 when he was dispatched to Hasbaya to inventory the assets of Yusuf's maternal uncle, Bashir ibn Najm, the son of Najm Shihab, leader of the Sunni Muslim, Hasbaya-based branch of the clan. Yusuf killed Bashir ibn Najm for backing the revolt against him led by Yusuf's brother Ahmad. During Bashir II assignment in Hasbaya, he married Bashir ibn Najm's wealthy widow, Shams. She was also known as "Hubus" (حبوس) and "Shams al-Madid" (شمس المديد), the latter of which translates in Arabic as "sun of the long day". Bashir II had previously encountered Shams on a hunting trip to Kfar Nabrakh, but at the time she was arranged by her father, Muhammad Shihab, to be married to Bashir ibn Najm. With the latter, Shams had a son named Nasim and a daughter named Khadduj. Although Bashir II was a Christian and Shams was a Muslim, members of the Shihab family typically married within the family and with the Druze Abillama clan, regardless of religion. As a result of his marriage to Shams, Bashir II gained considerable wealth. Shams later had three sons with him: Qasim, Khalil and Amin (listed in order of birth). Lady Shams al-Madid was the sister of the Emir Qa’dan son of Mohamad who resided in the village of 'Abayh in the Upper Gharb of Lebanon.

In 1829, Shams died, and Bashir had a mausoleum built for her nestled in the orchards of Beit el-Din. Afterward, a friend of Bashir from Sidon named Ibrahim al-Jawhari set out to find a new wife for Bashir. Al-Jawhari already knew a Circassian slave girl named Hisn Jihan in Istanbul. She was the daughter of a certain Abdullah Afruz al-Sharkasi, but had been kidnapped by Turkish slave dealers and sold to a certain Luman Bey, who was known to have treated her like a daughter. Al-Jawhari suggested that Bashir marries Jihan. Bashir agreed, but also instructed al-Jawhari to buy her and three other slave girls in case Jihan was not to his satisfaction. In 1833, al-Jawhari brought Jihan (then aged 15) and three other slave girls, Kulhinar, Shafkizar and Maryam, to Bashir. Bachir 2 was enthralled by Jihan, married her and built a palace for her in Beit el-Din.

Jihan was a Muslim and Bashir had her convert to the Maronite Church before the marriage. According to contemporary chroniclers of the time, Jihan was seclusive and only left her residence fully veiled, was a loving wife to Bashir, wielded significant influence over him and was reputed for her enchantment and charitable efforts with Mount Lebanon's inhabitants. She became known as sa'adat al-sitt, which translates as "her excellency, the lady". Jihan had two daughters with Bashir, Sa'da and Sa'ud. The other slave girls from Istanbul were married off to Bashir's relatives or associates; Kulhinar was married to Bashir's son Qasim, Shafkizar was married to Bashir's kinsmen Mansur Shihab of Wadi Shahrour and Maryam was married to a certain Agha Nahra al-Bishi'lani of Salima.

Bashir emerged on Mount Lebanon's political scene in the mid-1780s when he became involved in an intra-family dispute over leadership of the Shihabi emirate in 1783. In that dispute, Bashir backed emirs Isma'il and Sayyid-Ahmad Shihab (from Rashaya Branch) against Emir Yusuf (son of Mansur/Haydar and cousin of Qasim Shihab, the father of Bachir 2), who ultimately prevailed when the powerful Ottoman governor of Sidon, Ahmad Pasha al-Jazzar, confirmed his control of the Mount Lebanon tax farms after Yusuf promised him a bribe of 1,000,000 qirsh.

Bashir subsequently reconciled with Yusuf. Five years later, however, al-Jazzar attempted to collect Yusuf's promissory bribe, but payment of the large sum did not materialize, and al-Jazzar shifted his support to Yusuf's rival, Ali Shihab, Isma'il's son. Ali, who sought to avenge Isma'il's death in Yusuf's custody, and Yusuf mobilized their allies and confronted each other at Jeb Jannin, where Yusuf's forces were routed by Ali and al-Jazzar. Yusuf fled to the Tripoli hinterland and was compelled to request the Druze landowning sheikhs to appoint his replacement. With the key backing of the Jumblatt clan, Bashir was selected by the Druze sheikhs to be their hakim. For the Druze sheikhs of Mount Lebanon, the hakim denoted the leader prince who served as their intermediary with the Ottoman authorities, and who nominally had political, military, social and judicial authority over their affairs.

Bashir 2 traveled to al-Jazzar's headquarters in Acre, where he was officially transferred the Mount Lebanon tax farms in September 1789.

Meanwhile, Yusuf attempted to restore himself to the Shihabi emirate, mobilizing his partisans in Jubail and Bsharri, while Bashir 2 had the support of the Jumblatt clan (his main backer among the Druze) and al-Jazzar, who loaned him 1,000 of his Albanian and Maghrebi soldiers.

Bashir's forces decisively defeated Yusuf's partisans in the Munaytara hills, but Yusuf escaped after receiving cover from the Ottoman governors of Tripoli and Damascus. However, Yusuf was later invited to Acre by al-Jazzar in a ruse by the latter and was virtually under arrest upon his arrival to the city.

While al-Jazzar considered playing Yusuf and Bashir off of each other by soliciting bribes for the Mount Lebanon tax farm, Bashir managed to convince al-Jazzar that Yusuf was causing strife among the Druze clans, and al-Jazzar subsequently decided to execute Yusuf in 1790.

Despite prevailing over Yusuf, the Druze sheikhs of the Yazbaki faction (rivals of the Jumblatti faction) managed to lobby al-Jazzar to transfer the Mount Lebanon tax farms from Bashir to Yusuf's nephew, Qa'dan and Yusuf’s brother Haydar.

Not long after, Jirji Baz, the mudabbir (manager) of Yusuf's sons Husayn and Sa'ad ad-Din, persuaded Qa'dan and Haydar to grant Yusuf's sons the tax farm of Jubail. Bashir and his ally Sheikh Bashir Jumblatt resisted this situation by successfully preventing Qa'dan and Haydar from collecting the taxes that they were mandated to deliver to al-Jazzar. The latter lent Emir Bashir and Sheikh Bashir his support against Baz, Yusuf's sons and their Imad (leading clan of the Yazbaki faction) and Abi Nakad backers. Bashir succeeded in forcibly restoring himself as hakim, but by 1794, al-Jazzar again shifted his support to Baz and Yusuf's sons after Bashir apparently fleeced al-Jazzar in his tax payments that year. This was short-lived as al-Jazzar reverted to Bashir in 1795 after abundant complaints were raised against Baz.

In 1800, Emir Bashir appealed for unity with Baz, writing to him, "How long will this fighting continue in which we lose men and our land is devastated?" Baz agreed to meet Bashir in secret and the two reached a deal without al-Jazzar's knowledge, whereby Bashir would control the Druze areas of Mount Lebanon and Maronite-dominated Keserwan, while Yusuf's sons would control the northern areas, such as Jubail and Batroun. Bashir promised to uphold the agreement, swearing an oath on both the Quran and the Gospel. Bashir also hired Baz to be his mudabbir, replacing the Maronite Dahdah clan as his traditional provider of mudabbirs. Al-Jazzar was outraged when the agreement became apparent, and lent his support to the Yazbaki faction against the new alliance between Baz, Emir Bashir and Sheikh Bashir Jumblatt. For the next four years, the Yazbakis, led by the Imad clan, sponsored a rival Shihab emir to usurp the emirate, but failed each time. Most of the Druze sheikhs condemned the Imad clan in 1803 and rallied to Emir Bashir. Al-Jazzar died in 1804 and was ultimately succeeded by his former mamluk (manumitted slave soldier), Sulayman Pasha al-Adil.

With the relief of pressure from Sidon after al-Jazzar's death, Emir Bashir felt less reliant on Baz for maintaining power. Baz, meanwhile, had been asserting his influence in Mount Lebanon and often acted out of concert with Bashir, bypassing the latter's authority. Baz also formed an alliance with Maronite Patriarch Yusuf al-Tiyyan, to the chagrin of the Druze sheikhs, who perceived Baz's growing power as representative of the Maronite political upswing that grew at the expense of the Druze sheikhs, many of whom (including Sheikh Bashir Jumblatt), feared Baz. The Druze were also offended because Baz's power derived from his sponsorship by their overlord, Emir Bashir. The latter too had become irate over Baz's rising influence with the Ottoman governors, and felt particularly humiliated by Baz's canceling of a land survey of Keserwan ordered by Emir Hasan (Bashir's brother) and other humiliations regarding Baz's treatment of Emir Hasan. Bashir arranged to have Baz killed, recruiting Druze fighters from the Jumblatti and Yazbaki factions to commit the act. Thus, on 15 May 1807, Baz was ambushed and strangled on his way to Bashir's residence, while Bashir's Druze partisans occupied Jubail, killing Baz's brother and capturing and blinding Yusuf's sons. Afterward, Bashir sent assurances of loyalty to the governors of Tripoli and Sidon. Bashir also pressured Patriarch al-Tiyyan to step down.

With the elimination of Baz and Yusuf's sons, Emir Bashir consolidated his rule over Mount Lebanon.In 1810, Sulayman Pasha gave Bashir a leasehold for life over the Chouf and Keserwan tax districts, effectively making him the lifetime ruler of Mount Lebanon. Moreover, Sulayman Pasha would thereafter address Bashir in their correspondence with the honorary title of "pride of noble princes, authority over great lords, our noble son, Emir Bashir al-Shihabi". Circumstances that restricted his power at the time were the annual tax revenues due to Sulayman Pasha and the Jumblatt clan's domination over the other Druze sheikhs, who Sheikh Bashir protected from Emir Bashir's imposition of supplementary impositions.

By 1820, the Ottoman Empire was entering into war with Russia and attempting to quell a Greek uprising in Morea, prompting the Sublime Porte (Ottoman imperial government) to issue orders to Abdullah Pasha to fortify Syria's coastal cities and disarm Christians in his province. Abdullah Pasha believed only Emir Bashir was capable of fulfilling this task and sought to make way for his return to Mount Lebanon. To accomplish this, Abdullah Pasha ordered Hasan and Salman to promptly pay him 1,100,000 dirhams, a seemingly insurmountable levy. At the same time, Emir Bashir's allies in Mount Lebanon undermined Hasan and Salman, while Emir Bashir entered Jezzine, in the environs of Deir al-Qamar. Due to these factors, Hasan and Salman ultimately conceded to step down in favor of Bashir after mediation by 'uqqal (Druze religious leaders). According to the agreement reached on 17 May 1820, a referendum would be held among the inhabitants of Mount Lebanon regarding leadership of the emirate. Before the referendum could be held, however, Abdullah Pasha restored Bashir's authority on the condition that he collect the jizya for the Sublime Porte.

The Maronite peasants and clergymen of Jubail, Bsharri and Batroun decided to take up armed resistance against Bashir's impositions, and garnered the support of the Shia Muslim Hamade sheikhs. The peasants proceeded to assemble at Lehfed, Haqil and Ehmej, while Shia villagers assembled at Ras Mishmish. They selected wukkal for their districts, called for fiscal equality with their Druze counterparts, and declared a revolt against Emir Bashir. Among the leading wukkal was historian Abu Khattar al-Aynturini, who promoted the idea that the Shihabi emirate was a conduit for Maronite solidarity. Emir Bashir enlisted the support of sheikhs Bashir and Hammud Abu Nakad. With their Druze fighters, Emir Bashir forces the Maronites in northern Mount Lebanon to submit to his orders. The episode augmented the growing chasm between an increasingly assertive Maronite community and the Druze muqata'jis and peasants. According to historian William Harris, the "ammiya”, which expressed discordance between Bashir II's ambition and the interests of an increasingly coherent majority community, was a major step toward modern Lebanon. It represented the first peasant articulation of identity and the first demand for autonomy for Mount Lebanon.

In 1821, Bashir became entangled in a dispute between Abdullah Pasha and Dervish Pasha. The crisis was precipitated when the latter's mutasallim (deputy governor/tax collector) for the Beqaa Valley raided 'Aammiq’, when the latter's inhabitants denied him entry into the village.

Bashir attempted to mediate the dispute, and Dervish Pasha signaled his willingness to cede Damascus's traditional jurisdiction over the Beqaa Valley to Abdullah Pasha's Sidon Eyalet. Abdullah Pasha refused this offer and requested that Bashir take over the Beqaa Valley. Bashir accepted the task, albeit with reluctance, and under the command of his son Khalil, Bashir's forces swiftly conquered the region. Khalil was subsequently made mutasallim of the Beqaa Valley by Abdullah Pasha. In response, Dervish Pasha mobilized the support of the Yazbaki faction and a number of Shihabi emirs to reassert Damascene control over the area. However, Dervish Pasha's forces were defeated in the Anti-Lebanon Range and in the Hauran.

The Sublime Porte was troubled by Abdullah Pasha and Emir Bashir's actions against Damascus, and dispatched Mustafa Pasha, the governor of Aleppo Eyalet, to reinforce Dervish Pasha and help him defeat Abdullah Pasha. Mustafa Pasha sent an emissary to Mount Lebanon to announce an imperial decree dismissing Bashir from the Mount Lebanon tax farms, and reappointing Hasan and Salman. Afterward, Mustafa Pasha, Dervish Pasha and the leaders of the Yazbaki Druze persuaded Sheikh Bashir Joumblatt to defect from Emir Bashir in return for replacing Hasan and Salman with Abbas As'ad Shihab, which officially occurred on 22 July 1821. The governors' forces, backed by the Druze, proceeded to besiege Abdullah Pasha's Acre headquarters, and Emir Bashir left Mount Lebanon for Egypt by sea on 6 August, having lost the backing of his most crucial ally, Sheikh Bashir.

However, Emir Bashir gained a new, powerful ally in Egypt's virtually autonomous governor, Muhammad Ali. At the same time, Abdullah Pasha also requested support from Muhammad Ali, who saw in Emir Bashir and Abdullah Pasha the key to bringing Ottoman Syria under his hegemony. Muhammad Ali persuaded the Sublime Porte to issue pardons for Bashir and Abdullah Pasha, and to lift the siege on Acre in March 1822.

In return for Muhammad Ali's support, Bashir agreed to mobilize 4,000 fighters at the former's disposal upon request. Before returning to Mount Lebanon, Emir Bashir issued orders to Sheikh Bashir to pay a large sum of 1,000,000 piasters in return for a pardon, but Sheikh Bashir Joumblatt instead opted for self-exile in the Hauran. From there, Sheikh Bashir began preparations for war with Emir Bashir. Sheikh Bashir struck an alliance with his Druze rival, Ali Imad, head of the Yazbaki faction, the Arslan clan, the Khazen sheikhs of Keserwan, and the Shihab emirs who were opposed to Emir Bashir's rule. With 7,000 armed supporters, Sheikh Bashir entered Beit el-Din in a demonstration of power to force Emir Bashir to reconcile with him. Emir Bashir continued to insist that Sheikh Bashir make the full payment to compensate for his betrayal, prompting unsuccessful mediation attempts by various Druze and Maronite sheikhs and Maronite bishop, Abdullah al-Bustani of Sidon. Emir Bashir and Sheikh Bashir thereafter readied for war.

Emir Bashir experienced a setback when he clashed with Sheikh Bashir's forces on 28 December 1824. However, this loss was reversed following Abdullah Pasha's dispatch of 500 Albanian irregulars to aid Emir Bashir on 2 January 1825. Upon the arrival of the reinforcements, Emir Bashir launched an attack and routed Sheikh Jumblatt's forces near the latter's headquarters at Moukhtara. Afterward, Sheikh Bashir and Imad fled for the Hauran, and Emir Bashir pardoned enemy fighters who surrendered. Imad and Sheikh Bashir were subsequently captured by the forces of Damascus's governor, with Imad being summarily executed and Sheikh Bashir being sent to Abdullah Pasha's custody in Acre. Upon request from Muhammad Ali, who sought to ensure Emir Bashir's reorganization of Mount Lebanon went unhindered, Abdullah Pasha had Sheikh Bashir executed on 11 June.

Emir Bashir proceeded to reorganize the tax farms (virtual fiefs) of Mount Lebanon to strengthen the hand of his remaining Druze allies and deny his enemies a fiscal power base. As such, the Jumblatts were dismissed from the tax districts of Chouf, Kharrub, Tuffah, Jezzine, Jabal al-Rihan and the eastern and western Beqaa Valley regions, which were redistributed to Bashir's son Khalil, the Talhuqs, and Nassif and Hammud Abu Nakad. Furthermore, the personal residences and orchards of the Jumblatt and Imad sheikhs were destroyed. Bashir's campaign prompted many Druze to leave for the Hauran to escape potential retribution.

To centralize his rule over the emirate (as opposed to the previous bipartite regime with Sheikh Bashir), Emir Bashir proceeded to assume control over legislative and judicial powers by setting up a defined legal code based on the Sharia law of the Ottoman state. Moreover, he transferred jurisdiction over civil and criminal affairs from the mostly Druze muqata'jis to three special qudah (judges; sing. qadi), whom he personally appointed. As such, he assigned a qadi in Deir al-Qamar in Chouf, who mostly oversaw the affairs of the Druze, and two Maronite clergymen who were based in Ghazir or Zouk Mikael in Keserwan and Zgharta in northern Mount Lebanon, respectively. Although the new legal code was based on Sharia, Bashir did not seek to overturn deeply-entrenched customary law, and the qudah typically relied on local customs in their judicial decisions, and only referred to the Sharia as a last resort.

Emir Bashir's alliance with Muhammad Ali and his falling out with Sheikh Bashir, under whom's consent Emir Bashir had been able to rule Mount Lebanon for the preceding two decades, marked a major turning point in Emir Bashir's political career. Emir Bashir's loss of Druze support and his subsequent destruction of their feudal power paved the way for the strengthening of his ties with the Maronite Church. Moreover, Bashir looked to the Maronite clergy as the natural alternative to substitute the Druze in his new, highly centralized administration. Concurrently, he became more at ease with embracing his Christian faith since he no longer depended on Druze support. Patriarch Yusuf Hubaysh greatly welcomed the aforementioned developments.

Between 1825 and his demise in 1840, Bashir installed Maronite patriarchs, bishops, and lower-ranked priests as the principal functionaries of his administration and as advisers. In effect, Maronite clergymen, who had long dominated the religious and secular aspects of Maronite life, acquired the privileges that the Druze muqata'jis had previously maintained with Bashir and his Shihabi predecessors. The lower-ranked clergymen in particular obtained Bashir's sponsorship to help them rise through the hierarchy of the Maronite Church in return for their support and their efforts to promote loyalty and love for Bashir among the Maronite peasantry. These clergymen were also at the forefront of efforts to roll back the excesses imposed on Maronite tenants from their Druze lords and the latter's influence in the tax districts in general. Meanwhile, the remaining Druze muqata'jis continued to serve as the leaders of a Druze community that was increasingly resentful of Maronite ascendancy at the expense of Druze power. As a consequence of this situation, communal tensions between the Druze and the Maronites grew further. Throughout this period, the Ottoman government permitted Bashir's patronage of Maronite domination in Mount Lebanon.

Muhammad Ali sought to annex Syria, and as a pretext to invade the region, he published a list of complaints against Abdullah Pasha, who in turn received the support of Sultan Mahmud II. The latter had the mufti of Istanbul issue a fatwa (Islamic edict) that declared Muhammad Ali an infidel, while Muhammad Ali had the Sharif of Mecca issue a fatwa that condemned Mahmud II for violating the Sharia and promoted Muhammad Ali as Islam's savior, subsequently setting the stage for war between Egypt and Istanbul. Under the command of Muhammad Ali's son Ibrahim Pasha, Egyptian forces began their conquest of Syria on 1 October 1831, capturing much of Palestine before besieging Abdullah Pasha in Acre on 11 November. Bashir faced a dilemma amid these developments as both Abdullah Pasha and Ibrahim Pasha sent emissaries requesting his support.

Bashir initially hesitated in choosing sides, but once he received word that Ibrahim Pasha was prepared to mobilize six of his regiments to devastate Mount Lebanon and its lucrative silk industry, and that Sheikh Bashir Jumblatt's sons Nu'man and Sa'id had made their way to Ibrahim Pasha's camp to pledge their allegiance, Bashir deferred to the Egyptians. He ultimately concluded that Muhammad Ali was stronger and more progressive than the Sublime Porte and believed he would risk losing his emirate by challenging the Egyptians. Moreover, his Maronite and Melkite allies also favored Egypt because of its centrality to eastern Mediterranean commerce and the religious egalitarianism of Muhammad Ali. Meanwhile, under the Sublime Porte's orders, the mutasallims of Beirut and Sidon and the walis of Tripoli and Aleppo stood by Abdullah Pasha, and issued warnings to Mount Lebanon's notables to do likewise. Bashir attempted to rally his Druze allies and rivals, such as Hammud Abu Nakad and several Jumblatt, Talhuq, Abd al-Malik, Imad and Arslan sheikhs, to defect to Muhammad Ali. Instead, they joined the Ottoman army mobilizing in Damascus under the command of the serasker (commander-in-chief), Mehmed Izzet Pasha. The latter issued a decree condemning Bashir as a rebel and replacing him with Nu'man Jumblatt.

The alignment of the major Druze clans with the Ottomans compelled Bashir to further rely on his growing Maronite power base. He subsequently directed Bishop Abdullah al-Bustani to appoint a Maronite military commander for each district, but to do so discreetly to avoid provoking a Druze backlash. The Maronite commanders were tasked with tax collection, which was traditionally the responsibility of the mostly Druze muqata'jis, and to arm Maronite peasant fighters to suppress Druze dissent in Mount Lebanon. Concurrently, Bashir also had the properties of the pro-Ottoman Druze muqata'jis attacked or seized. On 21 May 1832, Egyptian forces captured Acre. Afterward, Bashir and Patriarch Hubaysh were ordered by Ibrahim Pasha to prepare their mostly Maronite troops for an assault against Damascus. Bashir's troops were commanded by his son Khalil, and together with the Egyptian army, they captured Damascus without resistance on 16 June, before routing the Ottoman army at Homs on 9 July. Khalil had previously fought alongside Ibrahim Pasha in Acre and Jerusalem. Khalil and his troops also participated in the Egyptian victory at Konya in southwestern Anatolia on 27 December.

With Syria conquered, Muhammad Ali launched a centralization effort in the region, abolishing the eyalets (provinces) of Damascus, Aleppo, Tripoli and Sidon (including Mount Lebanon) and replacing them with a single governorship based in Damascus. However, through his close alliance with Muhammad Ali, Bashir maintained his direct authority over the Mount Lebanon Emirate, preventing it from being subject to the Egyptian bureaucracy that centralized power in the rest of Syria. Moreover, he was offered the governorship of "Arabistan" (the territories of Syria), but declined to assume leadership over the region, which was then transferred to Muhammad Sharif Pasha. In 1832, Muhammad Ali rewarded Bashir by extending the latter's jurisdiction to include Jabal Amil, which Bashir assigned to his youngest son Majid, the northern tax district of Koura and the port cities of Sidon and Beirut. The latter had become the commercial outlet for Mount Lebanon's silk industry, Acre's successor as the political center of the Syrian coast and a principal residence for Egyptian officials, European consuls and Christian and Sunni Muslim merchants. Bashir was entrusted with police power over Mount Lebanon and the plains around Damascus. The expansion of his jurisdiction enriched Bashir with increased revenues to the point that his tribute from Syria was four times larger than that of Muhammad Ali.

As part of Muhammad Ali's centralization efforts, tax collection was official transferred from muqata'jis to the appointees of the central authorities in 1833/34. Bashir took advantage of this measure by confiscating the estates of the muqata'jis and assigning his relatives as the mutasallims of the various tax districts. As such, he appointed Khalil to Shahhar, Qasim to Chouf, Amin in Jubail, his brother Hasan's son Abdullah in Keserwan, his cousin Bashir in Tuffah and his associate Haydar Abillama in Matn.

Bashir suppressed several revolts against Muhammad Ali's conscription and disarmament policies in the mountainous regions throughout Syria in the service of Ibrahim Pasha. Because of Bashir's support for Muhammad Ali, his forces and allies in Mount Lebanon were allowed to keep their arms. The first major revolt suppressed was the peasants' revolt in Palestine, during which Muhammad Ali sent orders to Bashir to advance against Safad, one of the centers of the rebellion. Accordingly, Bashir led his troops toward the town, but before reaching it, he issued an ultimatum to the rebels demanding their surrender. The rebels sent a certain Sheikh Salih al-Tarshihi to negotiate terms with Bashir, and they ultimately agreed to surrender after another meeting with Bashir in Bint Jbeil. Bashir's Druze forces under the command of his son Amin, entered Safad without resistance on 18 July, making way for the displaced residents from its Jewish quarter to return. Between 1834 and 1835, Bashir's forces commanded by Khalil and his relatives also participated in the suppression of revolts in Akkar, Safita, the Krak des Chevaliers and an Alawite revolt in the mountainous region of Latakia. With the various rebellions quelled, resistance to disarmament and conscription by Muhammad Ali's administration was stifled for a few years.

Muhammad Ali's position in Syria was shaken again in 1838, during the Druze revolt in Hauran, which attracted the support of the Jumblatt and Imad sheikhs of Mount Lebanon and Wadi al-Taym. The Shihab emirs of Hasbaya, Ahmad and Sa'd al-Din, were commissioned to put down the Druze rebels in Wadi al-Taym led by Shibli al-Uryan, while Bashir was ordered to mobilize a Christian force in April. Bashir acceded to Ibrahim Pasha's levy request, organizing a force under the leadership of his grandson Mahmud, which subsequently was sent to reinforce Ahmad and Sa'd ad-Din in Hasbaya. Bashir's troops were ambushed by Druze forces commanded by rival Shihab emirs, Bashir Qasim and Ali of Rashaya. Khalil and his Christian troops later came to Mahmud's aid, forcing the flight of Shibli to Hauran. Khalil and Ibrahim Pasha later routed the forces of Nasir ad-Din Imad and Hasan Jumblatt in July. A month later, Ibrahim Pasha and Shibli negotiated an end to the revolt, whereby the Druze would be exempted from conscription, corvée and additional taxes. The Christians of Mount Lebanon were rewarded for their support for Ibrahim Pasha with the distribution of 16,000 rifles. By the revolt's end, tensions between Christians and Druze were further heightened as the two sects mostly fought on opposing sides.

The Ottomans and British took advantage of Egypt's severely weakened position in Syria due to the heavy loss of troops and skilled officers in the 1838 revolt. After two years of diplomatic wrangling between Muhammad Ali, the Ottomans, Great Britain, France, and Russia, a war effort by an Ottoman-European alliance against Muhammad Ali's control over Syria was launched. Bashir's Druze and Christian rivals and dissidents to his rule in Mount Lebanon were courted and armed in an initiative by the British Foreign Secretary, Henry Palmerston. With British-Ottoman support, an alliance of sheikhs in Mount Lebanon, including the Abu Nakad, Abillama, Khazen, Shihab, Hubaysh and Dahdah clans, Khanjar al-Harfush, Ahmad Daghir, Yusuf al-Shantiri and Abu Samra Ghanim, launched a rebellion against Bashir and Ibrahim Pasha on 27 May 1840. Bashir managed to temporarily suppress the revolt by confiscating property from the rebels, issuing threats and offering tax reductions to uninvolved Druze sheikhs in return for their support. Most Druze did not join the revolt in its early stage due to its mostly Maronite or pro-Christian leadership based in Matn, Keserwan and the Sahil. By 13 July, Bashir informed the Egyptian authorities that the revolt was suppressed, and handed over 57 of the revolt's leaders and participants, including Haydar Abillama and Fransis al-Khazen, who were exiled to Upper Egypt. Bashir also had his sons and subordinate commanders collect the rebels' arms and redistribute most of them to his ally and kinsmen, Sa'd al-Din of Hasbaya.

A European alliance consisting of Great Britain, Prussia, Russia and Austria backed the Ottomans, and through the British consul in Beirut, Richard Wood, sought to persuade Bashir to defect from Muhammad Ali in August 1840. This was after Wood, who had been accorded responsibility over settling Mount Lebanon's affairs by the Ottomans, had won over Patriarch Hubaysh with guarantees that the Ottomans would respect the privileges of the Maronite Church in Mount Lebanon. Bashir had previously been informed by the French consul that French expeditionary troops were set to land in Beirut to back Ibrahim Pasha, who by then maintained a force of 33,000 troops across Mount Lebanon under the command of Sulayman Pasha. Bashir maintained his loyalty to Muhammad Ali and rejected a total of three offers by Wood to defect to the Ottomans, including a warning by British diplomat Lord Ponsonby that Bashir should "make haste to return to your [duty] to the Sultan". The third offer by Wood came with a warning that British-Ottoman forces were on the verge of assaulting the Egyptians in Syria.

Meanwhile, Bashir's nephew, Abdullah Shihab of Keserwan, defected to the Ottomans, along with the Khazen and Hubaysh sheikhs after the Ottomans offered to compensate them and their subordinates with tax relief for their revolt against Bashir a few months prior and after realizing that French support for Muhammad Ali was limited to the diplomatic realm. Abu Samra and the Maronites of Batroun, Jubail, Bsharri and Koura also defected from the Ottomans. Allied European and Ottoman forces began the naval bombardment of Beirut on 11 September, while the forces of Bashir's cousin, Bashir Qasim of Rashaya, attacked Sulayman Pasha's forces in Beirut, Sidon and Acre. While Ibrahim Pasha headed for Mount Lebanon from northern Syria, allied forces set up headquarters in Jounieh, north of Beirut, and began distributing weapons to Bashir Qasim's rebels. By 25 September, allied forces had captured Beirut, Sidon and Haifa, Tyre, cutting off Egyptian sea access to Ibrahim Pasha's troops.

Still unable to solicit Bashir's defection, Sultan Abdelmajid I issued a firman (imperial decree) replacing Bashir with Bashir Qasim on 8 October. After a failed attempt to woo the Druze sheikhs to his side by promising them complete control of Keserwan, Ibrahim Pasha fled, while Bashir surrendered to the Ottomans on 11 October. Bashir offered the Ottomans four million piasters to be exiled to France, but his offer was rejected. Instead, he was given the choice between exile in Malta or London. Bashir chose the former, and departed Beirut for Malta, bringing with him Jihan, all of his children and grandchildren, his mudabbir Butros Karama, Bishop Istifan Hubaysh, Rustom Baz and 113 retainers. After an eleven-month stay in Malta, they departed again for Istanbul. Bashir remained in Istanbul until his death in 1850. He was buried in the Armenian Church in the Galata district of the city.

Bashir was the strongest of the Shihabi grand emirs, but his forty-year rule, together with outside pressures from the Ottoman imperial and provincial authorities and the European powers, caused the Shihabi emirate's undoing.

Bashir overturned the traditional system of governance in Mount Lebanon by nearly eliminating the feudal authority of the Druze and Maronite muqata'jis, the secular Maronite leadership, and the political strength of the Druze leadership in general, which had long formed the wellspring of the emirate's power.

Bashir's rule concurrently brought about the development of sectarianism in Mount Lebanon's politics. This first manifested itself during the Maronite ammiya (عاميّة) movement against Bashir's tax exactions in 1820, and/or with Bashir's elimination of Bashir Jumblatt and subsequent cultivation of the Maronite clergy as a new power base to replace the mostly Druze muqata'jis (مقاطعجي).

Bashir Jumblatt's execution endowed Bashir with undisputed political power in Mount Lebanon and was done out of political considerations, but was seen by the Druze community as an attempt by a Christian to eliminate the Druze.

Popular feelings of sectarian animosity were aggravated during Egyptian rule when Bashir utilized Maronite fighters to quell Druze risings, and later used Druze fighters to suppress Maronite risings towards the end of the Egyptian period. Historian William Harris summarizes that Bashir contributed to the creation of the modern state of Lebanon, writing:

For good or bad, and whatever his personal responsibility, Bashir II's half-century bequeathed the beginnings of modern Lebanon. These included the idea of an autonomous Lebanese entity, popular identification with sectarian community above loyalty to local lords, popular communal political representation, and sectarian tensions.

Bashir also overturned another aspect of the "social contract" in Mount Lebanon by "serving the interests of outsiders against those of his own people", according to Lebanese historian Leila Fawaz. Moreover, his reliance on the Ottoman governors of Sidon and his heavy involvement in their political struggles with the other governors of Ottoman Syria turned Mount Lebanon into "a pawn of regional politics beyond its control". Historian Caesar E. Farah asserts,

Without the domestic schemes of Bashir, which facilitated the Egyptian occupation of Syria, Lebanon presumably would not have become in 1840 the cockpit of the great powers. While he may not have created the question, Bashir did convert the country into the fulcrum for the disruption of Ottoman rule in the Syrian provinces. He not only ended the primacy of his house, but also prepared the country to be the apple of discord cast to the nations of the West.

Today, the Shihab family (also spelled "Chehab") continue to be one of the prominent families of Lebanon. The third president of the Lebanese Republic, Fouad Chehab (فؤاد شهاب), was a member of the family, descending from the Ghazir-based, Maronite line of Hasan, Bashir II's brother, as was former Prime Minister Khaled Chehab, who descended from the Hasbaya-based, Sunni Muslim branch of the family. Direct descendants of Bashir II live in Turkey and are known as the Paksoy family due to Turkish restrictions on non-Turkish surnames. Members of the Paksoy family are Sunni Muslims.

In 1751, after the death of Bashir 2, his second wife Hosn returned to Lebanon. She resided in Jieh where she built Saint Elie church in 1855. She died in Borj El Brajneh en 1855.

Youssef Shihab Reign (Governed 1770-1778).

(b.1748-d.1790)

Yusuf Chehab (1748–1790) was the autonomous emir of Mount Lebanon between 1770 and 1789. He was the fifth consecutive member of the Shihab dynasty to govern Mount Lebanon. Emir Yusuf was apparently raised as a Maronite Christian, but was publicly a Sunni Muslim. During Yusuf Shihab's rule, many members of the Shihab family converted to Christianity and Yusuf also began to rely on the support of the Maronite Christians

"In 1753, Emir Mulhim was ill and unable to govern. This led to a rivalry over succession between his brothers Ahmad and Mansur, while Mulhim and his nephew Qasim (The father of Bachir 2) sought to prevent either from assuming control over the emirate. When Mulhim died in 1759, Qasim became the administrator of Chouf district, although after paying a bribe, this authority was transferred to Ahmad and Mansur. The two brothers engaged in conflict in which Yusuf supported Ahmad. Emir Mansur prevailed by 1763, and Yusuf fled the Chouf to Mukhtara, the headquarters of the powerful Druze Jumblatt clan. Ali Jumblatt, an ally of Emir Mansur, protected Yusuf and offered to mediate the dispute between the two. After Emir Mansur refused Ali Jumblatt's offer and seized Yusuf's properties, Ali switched allegiance and backed Yusuf in his struggle for control of the emirate.

Also in 1763, a 16-year-old Yusuf, under the mentorship of his Maronite manager Sa'ad al-Khuri and with the political support of Governor Muhammad Pasha al-Kurji of Tripoli, led the Sunni Muslim and Maronite peasants of the Tripoli countryside in an uprising that drove out the Hamade landlords, who were Shia Muslims. Thereafter, Muhammad Pasha appointed Yusuf as administrator of Batroun and Jubail. Yusuf's acquisition of Hamade territory not only provided him a solid power base from which to fight against Emir Mansur, but also provided him with the Hamade's former role as patrons of the local Maronite clergy. This further strengthened their relationship with the Maronites since Yusuf already had the support of the Khazen family of Keserwan, a prominent family of the Maronite church."

"In 1768, a strong alliance was established between Nasif al-Nassar, the sheikh of the Metawali (Shia Muslim) clans of Jabal Amil in south Lebanon, and Zahir al-Umar, the autonomous Arab sheikh of Galilee and northern Palestine and head of the Zaydani clan. Together, they carved out a territory under their control and largely independent of Ottoman authority. Emir Mansur allied himself with them against the Ottoman governors of Sidon and Damascus, while Yusuf supported the Ottomans. Emir Mansur backed Zahir and Nasif in their alliance with Ali Bey al-Kabir of Egypt. Ali Bey dispatched his commander Abu al-Dhahab to launch an invasion of Damascus in 1770. When Abu al-Dahab suddenly withdrew from Damascus after defeating its governor Uthman Pasha al-Kurji, Emir Mansur's position became vulnerable when Uthman Pasha resumed the governorship. The Druze clans of Mount Lebanon withdrew their backing for Emir Mansur and Uthman Pasha transferred his governorship of Chouf to his loyalist Emir Yusuf. Uthman Pasha officially appointed Yusuf as emir of Mount Lebanon. Together with Uthman Pasha and his sons (Darwish Pasha, governor of Sidon and Muhammad Pasha, governor of Tripoli), Emir Yusuf sought to push Zahir and his Metawali allies out of Sidon, which they briefly occupied during the Egyptian invasion of Ottoman Syria.[7]

Emir Yusuf led an offensive against Nasif and Zahir in late 1771, but was decisively defeated. He failed to arrive and support Uthman Pasha when the latter attempted to launch an invasion of Galilee, but was routed by Zahir's forces at the Battle of Lake Hula. Yusuf sought to compensate for this loss by launching a campaign against the Metawalis at Nabatieh, but was routed by the Zaydani-Metawali alliance, losting some 1,500 of his Druze soldiers. Following their victory against Emir Yusuf, the allies captured Sidon from Darwish Pasha. Emir Yusuf and Uthman Pasha attempted to wrest back control of Sidon by assembling a troops backed by artillery and commanded by Ottoman officer Jezzar Pasha. The siege failed when the Russian Navy entered the conflict to back their ally Zahir. After Emir Yusuf's troops were bombarded by Russian ships, Zahir and Nasif's troops drove them out of the area and pursued them to Beirut, which the Russians also began to bombard until Emir Yusuf paid their admiral to cease their fire.[9]

By 1772, Zahir and his allies were firmly in control of Sidon. In order to prevent further encroachments in Lebanon by Zahir, Emir Yusuf requested the assistance of Jezzar Pasha, an Ottoman officer.[7] Emir Yusuf turned down a bribe of 200,000 Spanish reales from Abu al-Dahab to betray Jezzar and execute him.[10] Jezzar Pasha soon consolidated his own rule in Beirut and ignored agreements he had made with Emir Yusuf regarding the latter's authority in the city. Emir Yusuf and his Druze soldiers subsequently tried to dislodge Jezzar Pasha, but were unable to.[7] Thus, Emir Yusuf requested help from his erstwhile enemy, Zahir al-Umar, via his uncle Mansur who he had previously struggled against and replaced.[10] Zahir accepted the request and had his Russian allies bombard Beirut by sea on Yusuf's behalf until Jezzar surrendered and fled. Zahir's backing became handy once again when Emir Yusuf's authority over the Beqaa Valley was challenged by the governor of Damascus in 1773. Emir Yusuf's brother, Sayyid Ahmad, who had been the governor of Beqaa at the time, had robbed traveling merchants from Damascus in the Beqaa village of Qabb Ilyas. Emir Yusuf removed him from the Beqaa and was appointed in his place.

Jezzar Pasha became the governor of Sidon in 1776 after the Ottomans' elimination of Zahir al-Umar. Emir Yusuf was confirmed as the governor of Beirut, Chouf, Beqaa and Jubail. Moreover, Hasan Pasha, the Ottoman kapudan (commander of the Ottoman Navy) who led the offensive against Zahir in 1775, declared that Governor of Sidon's authority over Emir Yusuf was limited to the collection of the miri (Hajj tax). However, Jezzar Pasha ignored this order and took over Beirut in 1776 with the demand that Emir Yusuf pay three years worth of miri tax. Jezzar was later driven out by the Ottoman Navy. Nassar was captured and executed by Jezzar in 1780."

De Haydar and Bachir 2: Melhem, Mansour et Ahmad, Yousef

Melhem (1732-1754)

Ce règne fut des

plus heureux. Réussissant aussi bien dans le jeu diplomatique que l’emploi de

la force, Melhem réussit à récupérer plusieurs

provinces libanaises, à réduire de plus de moitié le tribut réclamé par le

sultan turque. Le prestige qu’il a acquit permit le

Liban de rester fidèle à sa vocation de lieu de refuge. Soucieux d’épargner au

pays les aventures, il fera de bonnes relations avec les pachas ottomans, ses

voisins, un principe de politique extérieure. C’est un véritable tour de force

que, dans l’ensemble, il réussit en dépit de l’humeur changeante des pachas,

sous-tendue par la permanence des mauvaises intentions de la sublime porte.

Néanmoins un concours exceptionnel de circonstances allait rendre certains

heurts inévitables.

Au cours de ce

18ème siècle, le Liban a assisté à un défile de pachas appartenant à la même

famille des Al-Azm, dans les trois villes de Saida,

Tripoli et Damas. A un moment donné (1734), l’on vit même trois frères, Assaad, Saad al-Din et Suleiman al-Azm occuper

respectivement et simultanément les trois pachaliks. Serrer le Liban comme dans

un étau constituait une grande tentation. Melhem a

été servi par la source rivalité qui couvait entre les trois frères et par le

besoin ou se trouvait chacun d’eux de recourir a

l’Emir libanais pour l’aider à consolider sa position, voire mater les

continuelles rebellions de ses administrés.

Evènements marquants du règne

Interventions au Liban-Sud

En 1743, Saad al-Din al-Azm, pacha de Saida,

appela Melhem au secours contre l’insubordination des

Chiites (Metoualis) de Jabal

Amel (Libans-Sud) qui, les armes a

la main, refusaient l’impôt. L’emir se mit en marche

à la tête d’une force importante. Rien qu’à l’annonce de son approche, les

rebelles se hâtèrent de faire leur soumission au pacha, lequel demanda au chef

libanais d’arrêter sa marche. Mais celui-ci ne l’entendait point de cette

oreille ; c’est par son canal que les rebelles devaient passer. Aussi

poursuivit-il son avance. Les Metoualis, sans doute

encourages en sous-main par le pacha, procédèrent a une mobilisation générale

qui ne donna que plus de retentissement a la victoire de l’émir a Ansar en

1743.

Droit d’asile

En 1739, il

n’avait pas hésité à accorder l’asile aux rescapés de la famille Fares, de la

région du Shakif (Beaufort), qui avaient cherché

refuge à Deir al-Kamar.

Plus tard, des

janissaires, fuyant les poursuites du pacha de Damas, se refugièrent chez les Yazbakis, Talhouk et Abdel Malak.

Sommé par le pacha de livrer leurs hôtes, les yazbakis

refusèrent. Situation délicate pour le grand émir, pressenti des deux côtés.

Droit d’asile d’une part, autorité de l’état osmanli mise en cause par les

mutins, de l’autre. Melhem s’en tira par une mise en

scène en trois actes.

1.

Il

envahit les fiefs des Talhouk et des Abdel Malak,

comme pour les punir, et les força à s’éclipser pour un temps.

2.

Fort

de cette manifestation, il obtint le pardon pour les mutins qui réintégrèrent

Damas

3.

Il

rappela les Cheikhs Yazbakis et les indemnisa

discrètement des dommages qu’il leur avait causés.

Récupération de la Bekaa

En 1748, Melhem

entra en conflit avec Assaad pacha al-Azm, gouverneur de Damas. Celui-ci crut pouvoir prendre son

adversaire de vitesse en opérant un raid éclair sur le Mont-Liban, à travers la

Bekaa, couvrant en une étape la distance qui sépare Damas de Bar Elias (au

centre de ladite plaine). Prévenu à temps, l’emir

occupa aussitôt les points stratégiques donnant accès a

la montagne, dont le célèbre passage de Mughayteh,

près du col de Baidar ; puis, ayant achevé sa mobilisation (en trois

jours), il dévala les pentes et tomba sur les troupes du pacha qu’il mit après

un combat acharné, en complète déroute. La paix fut rétablie moyennant la

cession du gouvernement de la Bekaa à Melhem contre

le paiement de celui-ci du tribut y afférant, sans oublier bien entendu, de

servir à Assaad Pacha, quoique vaincu, sa part du

marché. Pour compléter sa main mise sur la plaine fertile, l’émir déposa le

seigneur de Baalbak, l’émir Haydar

Harfouche qui avait pris part dans les rangs ottomans

à la bataille de Bar Elias, et le remplaça par son frère, l’émir Hussein Harfouche, allié du prince libanais. Rappelons que la

possession de la Bekaa présentait le triple avantage d’offrir des avant-postes

de défense de la montagne, de faciliter les communications avec le Wadi al-Taym et d’augmenter d’une

façon substantielle les revenus de l’imara. On y

retrouve l’une des constantes de la politique libanaise.

Acquisition de Beyrouth (1749)

Restait le problème d’accès a la mer. Depuis que Saida était devenu le siège d’un

pachalik (1660) et comme Tripoli l’était déjà dès le début de la conquête

ottomane, l’Imara ne disposait plus d’un grand port

pour son commerce exterieur et pour le contact,

qu’elle voulait large avec l’Europe. Melhem jeta donc

son dévolu sur Beyrouth qui était administrée, en 1749, par un haut

fonctionnaire turc, Yasin bey. Pour trouver un

prétexte à l’intervention prélude à l’annexion, le grand émir poussa le Cheikh

Chahine Talhouk à susciter des troubles dans la ville

et ses environs.

Yasin implora le secours des pachas voisins.

Mais ceux-ci ne purent lui fournir aucune assistance. Craignant une trop grande

et contagieuse détérioration de la situation, ils convinrent de s’en remettre

au prince libanais du soin de sauver la situation et lui donnèrent pratiquement

blanc-seing. Il en profita pour mettre la main sur la ville. Elle sera après

Deir al-Kamar, la seconde capitale des Chehab jusqu’au jour où Jazzar la

leur arrachera de force.

L’essor

des maronites

C’est

un phénomène majeur

dans la vie libanaise, tant dans le domaine intérieur que sur le plan

extérieur. Les causes en sont multiples.

1.

Un

taux de natalité relativement élevé

2.

L’évolution

générale dans les domaines politiques, économique et social entrainant un

phénomène de compénétration entre les différentes régions libanaises dont

bénéficièrent surtout les maronites.

3.

L’essor

de l’industries de la soie en particulier. Dans l’ensemble, le niveau de vie de

la montagne était loin d’être luxueux mais elle ne manquait pas du nécessaire.

Dans ces conditions, le budget des habitants était sensible à toute nouvelle

source de revenu. Jusque-là, l’huile constituait le principal produit à

l’exportation ; elle était fabriquée surtout dans le Gharb, ce qui pourrait

contribuer à expliquer la prédominance de cette région dans la vie libanaise,

un bon laps de temps. La plaine de Koura dans le Liban-Nord, avait aussi de

riches oliveraies. La soie vint disputer à l’huile la première place et se

répandit dans beaucoup de villages maronites.

Collège maronite de Rome

A partir

du 16ème siècle, la création par le pape Grégoire 13 du collège maronite de

Rome (1584) allait doter l’Eglise maronite d’un noyau de clergé instruit.

Certains des anciens de ce collège enseigneront au collège de France alors

appelé Collège des lecteurs royaux. Ils contribuèrent efficacement à mettre en

pratique les résolutions du synode libanais relatives à l’éducation.

Le rôle des

ordres religieux a été très important. La vie érémitique était pratiquée depuis

des siècles au Liban. En 1732, le Saint-Siège fit mettre au point les règles

monastiques et les confirma. Les écoles religieuses fréquentées par toutes les

communautés du pays, formèrent un précieux creuset d’unité nationale ; les

lettrés maronites étaient appréciés et recherches par les notables de toutes

les communautés. Celles-ci connaitront a

leur tour u essor culturel et leurs écoles seront également fréquentées par

tout le monde, formant autant de creusets bénéfique pour l’unité nationale.

L’essor pris par

les Maronites sera encore soutenu par les renforts constitués par l’afflux de

congrégations religieuses occidentales : Jésuites, lazaristes,

Franciscaines, capucines, carmélites…

Le synode Libanais (1736)

En 1736, se tint à Louaizé, dans le Keserwan, un synode qui réorganisa l’église maronite,

proclama le principe de l’enseignement obligatoire et gratuit et fit obligation

aux diocèses, paroisses et couvents d’entretenir les écoles et de subvenir aux

besoins scolaires des enfants peu fortunés. Les programmes adoptés et consignés

dans les actes même du synode étaient à la pointe du progrès pour l’époque.

Signalons à titre d’exemple, qu’entre autres matières d’enseignement prévues,

il y avait la géographie, la cosmographie, des éléments de droits, etc.

Il est à noter que c’est à l’émir Melhem et non

au Sultan Mahmout 1er que le Pape Clément

12 choisit d’écrire pour lui recommander le synode et que le prince libanais

réserva un accueil des plus positif à la demande du Pape. Le Liban se préparait

ainsi au rôle de pionnier qu’il jouera au 19eme siècle dans le grand mouvement

de renaissance culturelle – et concomitamment politique- arabe.

En même temps que des foyers culturels, les couvents étaient des fermes

modèles. Les moines furent des défricheurs infatigables et des maitres dans la

bonification des terres. Les chefs féodaux de toutes les confessions

échangeaient avec eux d’immenses domaines incultes contre des terres défrichées

et bonifiées, sans préjudice des dons gratuits, mobiliers ou immobiliers, dont

ils les gratifiaient.

Signalons aussi l’influence acquise par la France grâce au renouvellement

des capitulations, notamment celles de 1740, et dont les Maronites étaient les

principaux bénéficiaires en Orient. Ils trouvaient dans la France une puissance

tutélaire et la France, chez eux, une fidélité a

toute épreuve en même temps qu’une plateforme naturelle d’intervention pour

protéger éventuellement ses intérêts et étendre le rayonnement de sa culture.

Sous Louis 14 et Louis 15, plusieurs membres de la famille Khazen

furent nommés consuls e France. Plus tard, il y en aura de la famille Saad et

d’autres familles catholiques.

Fin de Melhem

(1754-1759)

Ni la fermeté, ni la diplomatie de Melhem, ni sa

bonté à l’égard de tous les Chehab n’ont pu le mettre

à l’abri des intrigues des siens avides de pouvoir. Ahmad, son frère germain,

et Mansour, son frère consanguin, étaient les plus acharnés. Melhem demeura inébranlable jusqu’au jour où, atteint d’un

mal incurable, il abdiqua en faveur des feux frères ambitieux, ses propres fils

étant encore mineurs.

En 1754 Melhem s’installa à Beyrouth, dans une

retraite définitive sans être totale. Les Duumvirs (Mansour et Ahmad) semblent

lui avoir laisse les mains libres dans cette ville.

Deux actes célèbres se rattachent à cette période.

En 1758, deux corsaires grecs ayant opéré un raid au cours duquel ils

capturèrent un bateau beyrouthin, il y eut une vive émotion parmi la population

musulmane de la ville. L’église des Franciscains fut profanée, leur couvent

saccagé. Melhem, qui se considérait responsable de

l’ordre et de la justice et qui tenait à sécuriser les européens établis au

Liban, fit arrêter et exécuter deux des principaux meneurs et restituer les

effets pillés.

Cette même année (1758), Melhem tenta de faire

reconnaitre par la Sublime Porte le droit de ses fils au trône de l’Imara. Il chargea son neveu Kassem Ben Omar (le père du

futur Bachir 2) d’une mission dans ce sens et le munit de lettres

d’introduction auprès des personnages influents à la Cour. Mais à peine arrivé

à Istanbul, Kassem assiste à un coup d’Etat sanglant et retourne bredouille.

L’année suivante (1759), Melhem mourut. De son

vivant, il aurait permis à ses enfants d’embrasser la foi maronite et l’on sait

que certains d’entre eux, sinon tous, le firent.

Mansour et Ahmad

(1754-1763-1770) – Le duumvirat (1754-1763). L’élimination d’Ahmad (1763)

Tentative manquée de Kassem Chehab

A la mort de

l’émir Melhem, son neveu Kassem (le père de Bachir 2)

revendiqua le pouvoir. Sur le plan du droit, il arguait de sa mission à

Istanbul pour se présenter comme le dépositaire des volontés du prince défunt.

Sur le terrain, il disposait de quelques troupes turques. Il attaqua Beyrouth

ou se trouvaient ses deux oncles, il aurait pu les faire prisonniers, mais

faute de pouvoir, savoir ou vouloir pousser plus loin ses premiers succès, il

les laissa échapper. Il ne tara pas à prendre compte de son isolement dans le

pays car, son seul soutien étant des éléments armés que les turcs avaient mis à

sa disposition, l’opinion publique se rangea du coté de ses oncles. Il préféra

alors céder, se contenta d’un petit fief, vint s’installer un moment à Hadath, près de Beyrouth, ensuite un peu plus haut dans la

montagne, à Ain Dara (un an), puis à Bchemoun (quatre

ans), avant de s’établir définitivement à Ghazir, où

il se convertit au christianisme et où il mourut en 1768, peu après la

naissance de son fils Bachir 2 qu’il fit baptiser dans le rite maronite.

Mansour contre Ahmad

Après la mort de Melhem, le conflit ne tarda pas à éclater entre les

duumvirs. Il prit de l’ampleur et se compliqua de la rivalité clanique des joumblattis et des Yazbakis qui

vint s’y greffer, les premiers prenant parti pour Mansour, les seconds pour

Ahmad. L’étincelle partit, semble-t-il, d’une altercation entre les deux frères

au cours d’une partie de chasse. A la suite de l’incident, Ahmad se retira à

Deir Al-Kamar, Mansour à Beyrouth d’où il se hâta

d’offrir les présents d’usage en telle circonstance. Le pacha lui envoya des

troupes qui, se joignant aux siennes, lui permirent de marcher sur Deir Al-Kamar.

Mansour seul émir

Ahmad alerta ses

alliés Imad et Talhouk. Mais devant les forces

rassemblées par Mansour, ils préférèrent ne pas risquer. Isolé, Ahmad céda

(1763). Il obtint le pardon et, a conditions de ne plus se mêler des affaires

publiques, l’autorisation de s’installer à Deir El-Kamar.

Il y mourut en 1770

Mansour seul face à son neveu

Youssef

Après s’être

débarrassé de son frère Ahmad, Mansour s’appliqua à conjurer le danger que

représentait pour lui son neveu Youssef, fils de Melhem.

Celui-ci avait confié l’éducation de ses enfants mineurs à la famille de

Saad El-Khoury. L’ainée, Youssef, se faisait remarquer par son intelligence, sa

sagesse, son courage et cela inquiétait son oncle. Celui-ci décida brusquement

de confisquer les biens de ses neveux, les acculant à chercher refuge auprès

des Chehab de Wadi Al-Taym.Dees princes Chehab

intervinrent avec Cheikh Ali Joumblatt comme médiateur. Mansour accepta de

lever le séquestre et autorisa Youssef à quitter Wadi

Al-Taym et à résider auprès de son oncle Kassem (Le

père de Bachir 2) alors installé à Bchamoun. La

partie de l’accord concernant les personnes fut respectée, non celle relative

aux biens. Des lors Youssef se considéra délié de ses

engagements et quitta sa résidence forcée de Bchamoun

pour aller à Damas dont le gouverneur, Osman Pacha, lui réserva un accueil

bienveillant et l’adressa à son fils méhemét, pacha

de Tripoli. Une amitié allait naitre entre l’émir et les deux pachas, qui aura

des conséquences importantes au Liban.

En même temps,

Cheikh Ali Joumblatt, qui avait gagne en médiateur et

qui en voulait de n’avoir pas tenu parole, prenait le parti de Youssef. Un fort

courant de sympathie s’empara de l’opinion en faveur de Youssef et porta Mhemet pacha à lui accorder le « gouvernement des

régions de Jbeil et de Batroun » (1763). Mansour

dut s’incliner, heureux de garder le trône de l’Imara.

L’ascension de l’émir Youssef

(Il a gouverné entre 1770-1778). (b.1748-d.1790)

Youssef s’avéra un gouverneur aussi énergique qu’habile. Soutenu par le

pacha de Tripoli, il put contenir les Hamadé. Puis

les ottomans, pratiquant une politique de bascule, changèrent de camps. Alors,

l’Emir Youssef, soutenu par la masse du peuple et appuyé par les Joumblatt et

les Nakad, passa à l’offensive et eut raison de la

coalition Hamadé-Ottomans, en gagnant notamment la

bataille d’Amioun en 1770. Victoire que le vainqueur

a su exploiter en provoquant, contre les Hamadé, un

soulèvement quasi général, qui lui permit de les rejeter dans la Bekaa et de

les y poursuivre. Dans la foulée de l’avance de l’émir, des noyaux de villages

chrétiens s’installèrent sur le versant est du Mont Liban. Ces exploits ont

constitué pour Youssef un tremplin qui devait lui permettre d’accéder à l’Imara suprême. Youssef fut le premier Chehab

à se convertir au christianisme en 1754.

La guerre turco-russe

(1768-1774) et ses retombées au Liban

Ce fut une guerre

entre un empire encore mal structuré mais a l’ardeur juvénile et un empire

sénile dont la structure était décadente et qui méritera bientôt le surnom de

l’ « Homme malade ». Les Russes décidèrent d'ouvrir un front de

diversion, Pour la première fois, ils envoyèrent une flotte dans la

Méditerranée. Elle était placée sous les ordres de l'amiral Spiridov

mais commandée effectivement par l'anglais Elphinstone. Le commandement en chef

de toutes les forces tsaristes opérant dans le Levant appartenait au comte Orlof; favori de Catherine 2. En juillet 1770, la flotte

ottomane est écrasée à Tchesmé, laissant aux Russes

l'entière liberté de manœuvre en Méditerranée. Orlof

mit aussitôt à profit sa victoire. Après avoir soulevé les Grecs, il entra en

contact avec Daher al-Omar, chef de la tribu arabe des Banou

Zeidan, établie en Palestine, ainsi qu'avec Ali bey

le Grand. Chef mamelouk de l'Égypte ottomane. Les deux chefs aspiraient à

secouer le joug turc. Une sorte d'alliance fut conclue. En 1770, Ali Bey

dirigea sur Damas une expédition ayant à sa tête son meilleur lieutenant

Mohammed Abou al-Dhahab. Le gouverneur Osman pacha

prit la fuite et se réfugia à Homs. Mais Abou aI-Dhahab

se laissa gagner par les Ottomans ; il se retira de Damas et retourna en Égypte

ou il ne tarda pas à entrer en conflit avec son maître Ali bey et à l'obliger a fuir vers le Sinaï, puis en

Palestine auprès de son allié Daher al-Omar.

Le Liban dans la tourmente

Pressenti par son

ami et allié kaysite Daher

al-Omar, l'émir Mansour protesta de ses bons sentiments, mais préféra suivre

l’évolution de la situation avant de se prononcer. Lorsqu’il apprit l’entrée

d’Abou al-Dhahab à Damas, il lui envoya

ostensiblement trois chevaux richement harnachés, accompagnés de compliments

grandiloquents selon l'usage et le style de l'époque. De son côté, Osman pacha,

de Homs où il s'était retiré, appela au secours son ami l'émir Youssef.

Celui-ci commença aussitôt ses préparatifs, mais sans se hâter. C'est à Damas,

après le départ d'Abou a-Dhahab qu’il rejoignit, à la

tête de ses hommes, Osman pacha, lui affirmant qu’il n'avait pas attendu

l'abandon de la ville par le chef mamelouk pour se mettre en marche et que

c'est seulement après avoir atteint la Békaa qu'il

apprit la bonne nouvelle. Le pacha ne semble pas avoir mis en doute ses affirmations

et lui réserva un brillant accueil.

Le congrès de Barouk

Les Libanais

tirèrent la leçon des événements : la présence de Mansour à la tête de l'Imara ne pouvait qu'être compromettante à Istanbul. Or le

sultan semblait l'emporter. Une assemblée représentative des Libanais fut

convoquée à Barouk (1770). Elle accepta l'abdication

de Mansour et élit à sa place son neveu Youssef, qui jouissait par ailleurs

d'un puissant courant de sympathie populaire et était de surcroît bien vu des

Ottomans.

Youssef : Débuts

difficiles. Série de revers

Les débuts de

l'émir, en plein tourmente internationale, furent difficiles. Il avait embrassé

le parti de la Sublime Porte à un moment où l'avance russe retenait toutes les

forces du sultan en Europe, ce qui laissait le champ libre aux énergiques

rebelles Daher al-Omar et Ali bey. Celui-ci, quoique évincé du pouvoir,

disposait toujours de troupes d'élite peu nombreuses mais redoutables. Quant à

Daher, il avait gardé sa puissance intacte. Au surplus, la flotte russe allait

entrer en action, faisant pencher la balance, pour un laps de temps, en faveur

de ses protégés. A peine rentré à Damas (1770), Osman pacha voulut exploiter la

défection d'Abou al-Dhahab pour punir Daher al-Omar. À la tête d'une armée qualifiée de « nombreuse

» par les chroniqueurs, il marcha contre lui. Alerté à temps, Daher l'attendit

à l'entrée de la Palestine, près du lac Houlé et lui

infligea une cuisante défaite. Les Turcs perdirent un grand nombre de tués,

noyés, disparus ou prisonniers, sans compter les blessés.

Querelles avec les Métoualis

Les Métoualis, alliés de Daher,

envahirent les terres de l'émir Youssef. Celui-ci usa de représailles (1771) en

attaquant et ravageant une partie du Jabal Aamel. Il s'apprêtait à marcher sur Nabatié.

Il a eu le double tort de repousser toutes les offres de réconciliation et de

ne pas attendre, pour attaquer, l'arrivée des renforts que lui amenait son

oncle, l'émir Ismaïl Chéhab. Il subit un désastre

complet à Nabatié. Il a fallu l'arrivée des troupes fraîches

amenées par Ismaïl pour arrêter la marche des vainqueurs sur le Chouf.

Cependant Daher occupa Saida, abandonnée par Youssef et ses alliés, et y

installa une garnison de Barbaresques.

Bataille de Saïda-Ghaziyyeh

(1772)

En 1772, l'émir

Youssef et les Ottomans tentèrent de regagner le terrain perdu. Les troupes des

pachaliks de Damas et de Tripoli se joignirent à celles de l'émir pour marcher,

ensemble sur Saïda. La flotte russe intervint. Ses canons jetèrent le désordre

dans les rangs de leurs ennemis ; la fougue des mamelouks d'Ali bey et l'élan

des hommes de Daher firent le reste (22 mai 1772) : victoire complète à la

suite de laquelle la domination de Daher s'étendit de Saïda jusqu'au sud de la

Palestine. Peu après, la flotte russe bombarda Beyrouth, deuxième résidence des

Chéhab. Il a fallu l'entremise de Mansour Chéhab auprès de son ami Daher al-Omar et le paiement de 25

000 piastres aux Russes pour obtenir le retrait de leurs vaisseaux.

Ahmad al-Jazzar à Beyrouth

Pour prévenir un

retour de la flotte ennemie, les Ottomans décidèrent de fortifier Beyrouth.

Sans ménagement pour leur allié libanais, ils nommèrent comme gouverneur de la

ville, chargé de la fortifier. Ahmad Al-Jazzar,

ancien mamelouk d'origine bosniaque, qui avait quitté le service d'Ali bey pour

rejoindre le camp ottoman. Son tempérament sanguinaire et ses nombreux crimes

lui valurent le triste surnom de Jazzar (« boucher

»). Malgré les mises en garde de son oncle l'émir Mansour, Youssef accepta le

fait. D'aucuns avancent l'hypothèse que c'est sa méfiance à l'égard de son

oncle qui lui dicta cette attitude. La cruauté et le cynisme légendaire de Jazzar vont se doubler d'une ingratitude noire à l'égard de

Youssef. Il entreprit bien la fortification de Beyrouth, mais pour son propre

compte. Quant Youssef s'en aperçut, il était déjà trop tard. Seul, il ne

pouvait rien contre l'usurpateur. De nouveau, il se tourna vers son oncle

Mansour et Cheikh Daher, et négocia, par leur intermédiaire, une nouvelle

intervention de la flotte russe. Daher, récemment installé à Saïda, ne voyait

pas d'un bon œil le voisinage de Jazzar à Beyrouth.

Il intervint volontiers et la flotte russe revint bombarder la ville. Les

fortifications tinrent bon. Il a fallu entreprendre un siège en règle. A court

de provisions, la place se rendit au bout de quatre mois. Jazzar

se réfugia auprès de Daher qui le prit à son service.

Youssef perd définitivement Beyrouth

Persévérant dans

la déloyauté, Jazzar ne tarda pas à trahir Daher, lui

enleva un riche convoi et, fortune faite, alla se réfugier à Damas et, de là

gagna Istanbul. Pour le récompenser et d'avoir trahi la cause de Daher et

d'avoir offert à la Cour de riches cadeaux provenant de ses nombreuses rapines,

la Sublime Porte lui confia un pachalik en Asie Mineure. Pendant ce temps, la

guerre turco-russe prenait fin par le traité de Mainardji

(1774) et les vaisseaux de la tsarine quittaient la Méditerranée. La flotte

ottomane retrouva la maîtrise des eaux du Levant et le capoudan

pacha Hassan vint assiéger Daher dans Akka. Usant de ruse autant de force, il

l'accula à abandonner la place. Au cours de sa tentative fuite, Daher fut tué.

Alors Jazzar fut transféré à Saïda (1775). Son

premier soin fut de réoccuper Beyrouth. L'émir Youssef obtint du capoudan pacha un ordre intimant à Jazzar

de quitter la ville. Il fut transféré par voie de mer à Saida, la garnison

devant le rejoindre par voie de terre. Youssef conçut le malheureux projet de

tendre une embuscade aux hommes de Jazzar près de Saadiyyat, entre Beyrouth et Saïda. Le coup échoua

lamentablement et, la flotte s'étant éloignée, Jazzar

réoccupa Beyrouth pour ne plus en sortir. Après la chute de Daher al-Omar, il

transféra sa résidence à Akka qu’il se hâta de rendre inexpugnable par la

construction de puissantes fortifications. Désormais il sera plus connu

Youssef et Jazzar. Série de

conflits

De 1775 à 1790,

l'histoire du gouvernement de Youssef se confond presque avec celle de ses

relations avec Jazzar dont les crises et le cynisme

ne faisaient qu'augmenter avec l'accroissement de sa puissance. Il devint comme

possédé par une manie de la persécution Énergique, réaliste, maître dans

l'intrigue, exploitant à merveille les zizanies entre les Libanais, achetant

les personnes influentes à la cour du sultan, il se maintiendra dans son

pachalik une trentaine d'années (1775-1804) et sera un des rares gouverneurs à

mourir de mort naturelle (1804), après un parcours qui fut un long cauchemar

pour le Liban. Ses cibles préférées étaient l'Imara

du Liban, les Métoualis du sud et surtout les

Chrétiens. Un tel programme ne pouvait malheureusement pas déplaire à Istanbul.

Pire, il a pu être une des raisons de l'exceptionnelle longévité du

gouvernement de Jazzar. A quatre reprises même, il

obtint de la Sublime Porte, en plus d' Akka, le

gouvernement de Damas comme pour lui permettre de mieux enserrer la Montagne.

Ses intrigues et ses violences, le poids des impôts extorqués ont acculé l'émir

Youssef quatre fois à l'abdication, non sans résistance armée et parfois

victorieuse. Mais toutes ses exactions, tous ses raffinements de tyrannie

barbare (incendie des demeures des Chéhab à Beyrouth,

meurtres, profanation d'églises...) ne vinrent pas à bout de la ténacité des

Libanais C'était généralement des soulèvements populaires qui rétablissaient le

prince sur son trône : « Au Liban, dira Lamartine dans les années 1830, il y a

un peuple. »

Pour juger

équitablement le comportement de Jazzar, il faut

faire la part des mœurs de l'époque. L'émir Youssef lui-même s'est parfois

montré implacable dans sa vengeance, violent et même cruel. De propre main, il

tua son frère Effendi, arrêté à la suite de la découverte d'un complot dans

lequel il avait trempé ; un autre frère, Sayed Ahmad, eut les yeux

crevés ; deux cousins Chéhab de Wadi al-Taym furent l'un, Béchir exécuté

en présence de Youssef, l'autre jeté en prison puis étranglé. Le grand drame

éclata en 1788. Une révolte des hommes de Jazzar

faillit renverser le sanguinaire pacha. Mais leurs divisions d'un côté, et

l'énergie et l'astuce du tyran de l'autre eurent raison de la rébellion.

Cependant Youssef avait commis l'imprudence de se montrer favori aux mutins. Le

conflit était inévitable. - Jazzar marcha sur le

Mont-Liban par la Békaa. Youssef se porta à sa

rencontre. Après un premier succès, il subit deux défaites, à Jennine et Kab Elias, à la suite

desquelles il se replia dans la Montagne pour refaire ses forces, après avoir

confié la défense des confins à son petit cousin Béchir ben Kassem (le futur

Béchir 2), assisté de Kassem Joumblatt. Mais, très vite, il conçut, non sans

raison, des doutes sur la loyauté de ces deux seigneurs. Et comme, d'autre

part, ses lourdes impositions fiscales lui avaient aliéné la population, ses

chances de résister se trouvaient plus que compromises. Il jugea plus sage de

s'en remettre à un congrès national.

Congrès de Barouk (1788)

Le congrès se

tint à Barouk, aux lieux mêmes où, il y avait quelque

vingt ans, un autre congrès l'avait élevé au trône à la place de son oncle

Mansour. Devant l'assemblée, Youssef expliqua l'impossibilité dans laquelle il

se trouvait de garder le pouvoir et demanda aux notables réunis de lui choisir

un successeur. Il souhaitait que ce fût Béchir ben Kassem, espérant rester,

face à un jeune prince (vingt et un ans), intrigant mais inexpérimenté, le véritable

maître du pouvoir. Une autre version — qui ne contredit pas la précédente —

veut que Youssef, fatigué, découragé et devenu très méfiant à l'égard de Jazzar, ait préféré abdiquer directement en faveur de

Béchir, dans l'espoir de pouvoir ressaisir le pouvoir rapidement et que, mis en

garde contre le dangereux jeune prince, il ait répondu « À la limite, je dirais

que si Béchir devait la [l’Imara] manger [dans le

sens figuré de : la prendre], je préfère encore que ce soit un lion [Béchir]

plutôt qu'une hyène [un quelconque émir médiocre]. » Quoi qu'il en soit, Béchir

ben Kassem fut élu à l'unanimité et allait inaugurer un long règne de près d'un

demi-siècle, tourmenté et parsemé d’événements majeurs, voire de tournants

décisifs et de malheurs, tout en ne manquant pas de grandeur et de moments de

très grand prestige.

Fin de l'émir Youssef (1790)

Aussitôt élu,

Béchir prit le chemin d'Akka, où le gouverneur Ahmad pacha (Jazzar)

l'accueillit avec égards, le reconnut prince suprême de son pays et lui

recommanda d'éloigner l'émir Youssef, son prédécesseur. Ce n'était que

l'ouverture d'un scénario qui se répétera et durera autant que le pacha. La

tactique de ce dernier sera d'éviter à tout prix l'union des Libanais. Il saura

exploiter, avec un art consommé leur « soif du pouvoir » que décrit avec

finesse le missionnaire américain John Carne. Sa politique sera celle de la

bascule qu'il va manipuler avec beaucoup d'adresse, dressant les uns contre les

autres, soutenant l'un puis l'autre et arrachant, à chaque volte-face, un

surplus de tribut. L'absence d'une règle expresse et ferme réglementant la

succession au trône princier facilitera sa tâche. De retour à Deir al-Kamar, Béchir reçut l'hommage des principaux féaux. Il fit

part à Youssef des mauvaises dispositions de Jazzar à

son égard et lui conseilla de partir pour le Kesrouan.

Puis il se mit en marche comme s'il le pourchassait en exécution de la volonté

du terrible pacha. De son côté, Youssef se retirait à distance devant les

troupes du nouvel émir suprême.

Soudain les

choses se gâtèrent. Youssef, qui n'avait renoncé au trône qu'à contrecœur, se

montra sensible aux pressions de ses partisans qui le poussaient à reprendre le

pouvoir. La région de Jbeil lui était restée fidèle

ainsi qu'une partie du Metn, du Kesrouan

et de Bcharré ; les Hamadé,

réconciliés, favorisaient sa cause. Il ébaucha un mouvement de regroupement des

éléments de son clan restés loyalistes. La réaction de Béchir ne se fit pas

attendre. A la tête de ses hommes et des renforts envoyés par Jazzar, il marcha résolument contre Youssef qui se hâta de

quitter le Liban. Il s'établit, pour un moment, dans la région de Zabadani, non loin de Damas. Après huit mois d'exil

volontaire, il réapparut dans le « pays de Jbeil ».

De là, il se dirigea brusquement sur Akka, sans doute après en avoir aplani le