The secret of the House of Maan

Summary:

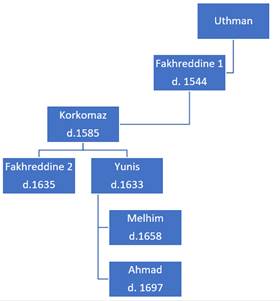

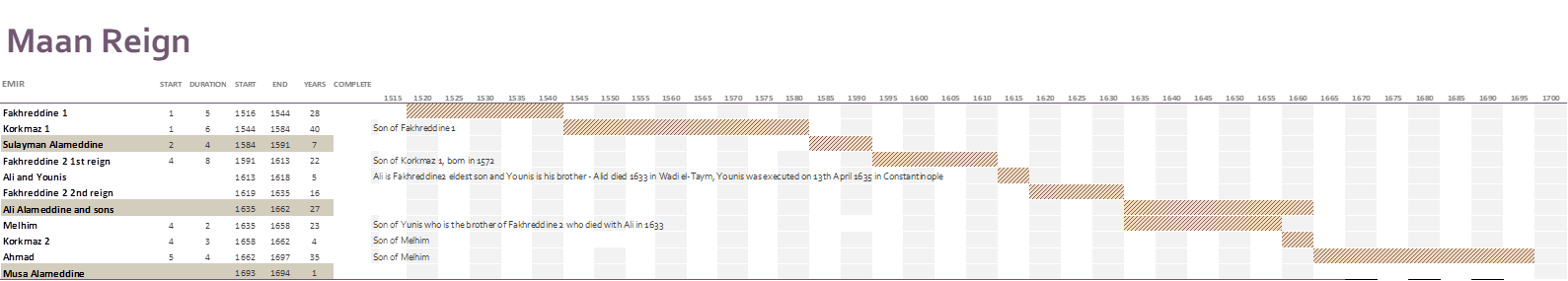

This research, conducted by Dr. Kamal Salibi[1], lead to a conclusion that the Maan genealogy as constructed by the 17th and 18th centuries historians might not be very accurate. Salibi suggests that much history was suppressed to accommodate the political interests on the Maanid house of Korkomaz and its Shihab successors. Historians Emir Haydar[2] Shihabi and Tannous Shidyak[3] , puzzled by the prolonged rule of Korkomaz Maan in the Shouf (84 years), introduced for him as father and predecessor a Fakhreddine 1 who died in 1544

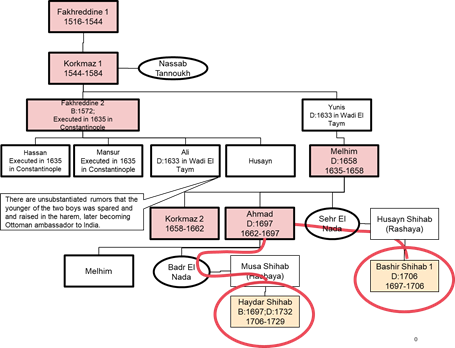

The Maan genealogies as seen by Haydar Shihab & Tannous Shidyak and Kamal Salibi

|

Maan Genealogy as constructed by Haydar Shihab and

Tannous Shidyak |

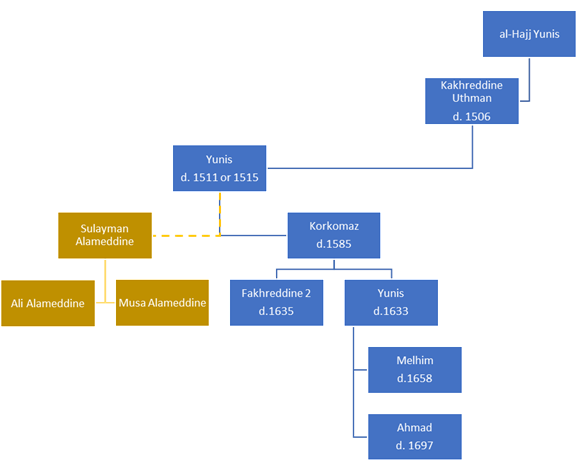

Maan Genealogy as suggested by Dr. Kamal Salibi |

|

|

|

Salibi postulates that:

· Fakhreddine 1 never existed. There was never a Fakhredine Ibn Uthman, but a Fakhreddine Uthman who died 10 years before the battle of Maj Dabik where Sultan Selim 1 conquered Syria and Lebanon.

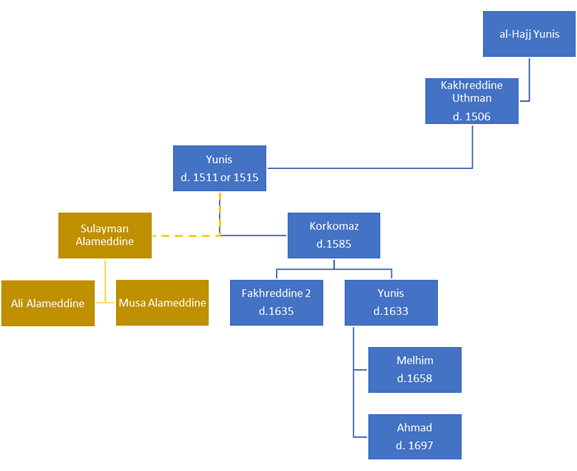

· Qorkomaz (d. 1585) was the son Yunis (d. 1511 or 1512). Yunis was the son of Fakhreddine Uthman (d. 1506). Fakhreddine Uthman was the son of Yunis.

· The Maanid emir who was supposedly confirmed by the ottoman conqueror in the chieftainship of the Shuf was identified by Estephan Duwayhi as a Korkomaz ibn Yunis, not as Fakhreddine ibn Uthman or Kakhreddine 1.

· Ali Alameddine was related to Korkomaz. He could have been a paternal or maternal uncle, a cousin close enough to be associated with him in the leadership of the family, or even a brother (unlikely)

· The descendants of Korkomaz preferred to have Ali’s memory suppressed

· Historians overlooked the existence of the Alameddine intentionally to accommodate the political interests of the Maanid house of Korkomaz and its Shihab successors.

· There were two branches of the Maanid family, a house of Korkomaz and a house of Alameddine. This means that the Maanid male line would not have died out with the death of Emir Ahmad in 1697 but would have survived in the house of Alameddine which was established in exile in the outskirts of Damascus.

· The claim of the Alameddine, especially if they were Maanid, would have been the stronger one to the succession. When the Alameddine, in 1698 and in 1710-11, returned to the southern Lebanon to attempt the overthrow of the Shihabs, the justification of their return might well have been the reclamation of the Druze emirate from the Sunnite and alien Shihab line for their own more legitimate Maanid line. As it was, however, the Alameddine were defeated and exterminated by the Shihabs in the battle of Ain Dara, and the basis of their claim to the emirate, whatever it may have been, was again suppressed, or merely forgotten. The conspiracy of silence against the Alameddine, so clearly observable under the Maans, continued under the Shihabs.

· The Maanid emir who was supposedly confirmed by the ottoman conqueror in the chieftainship of the Shuf is identified by Duwayhi as a Korkomaz ibn Yunis, not as Fakhreddine ibn Uthman.

Introduction

The History of the Lebanese mountain from the 16th to the 19th century relies on four main sources:

1. Hamza Ibn Sibat (?-1520): (حمزة إبن سبات)He is the son of Shihab al-Din Ahmad Ibn Sibat from Aley. He is a historian who is known for having chronicled events of the years 1132-1520. He is also known for his poetry as well as for his biographical account of Druze sages, such as that of Emir Al Sayyid al-Tannukhi.

2. Istifan al-Duwayhi (1630-1704): (Arabic: اسطفانوس الثاني بطرس الدويهي August 2, 1630 – May 3, 1704) was the 57th Patriarch of the Maronite Church, serving from 1670 until his death. He was born in Ehden, Lebanon. He is considered one of the major Lebanese historians of the 17th century and was known as “The Father of Maronite History”.

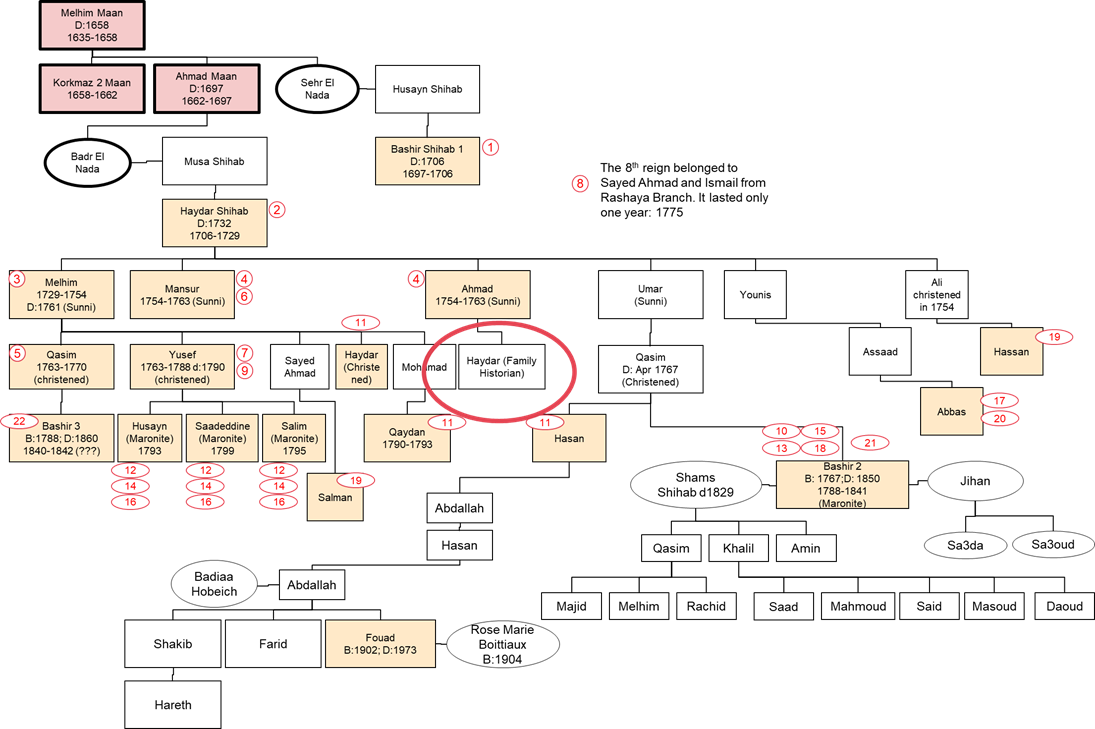

1. Haydar Shihab (died in 1835): He was the Emir historian Haydar Shihab who wrote الغرار الحسان في تاريخ حوادث الزمان. Haydar was the son of Ahmad Shihab (died 1763) and Ahmad was the son of Haydar (died in 1729) who succeeded to Bachir 1 on the chieftainship of Mount Lebanon

2. Tannous Shidiac الشدياق طنوس (died in 1861): Tannous was a former assistant and disciple of Haydar Shihab. He wrote أخبار الاعيان في جبل لبنان (History of the nobles in Mount Lebanon). It was a compilation of genealogy and history

To note that Patriarch Istfan Duwayhi was a close friend to Ahmad Maan: the last Emir from the Maan dynasty.

Haydar Shihab was the grandson of Emir Haydar Shihab (d. 1732), and Tannus whas Haydar’s disciple.

Are the Alameddins a branch of the Maan?

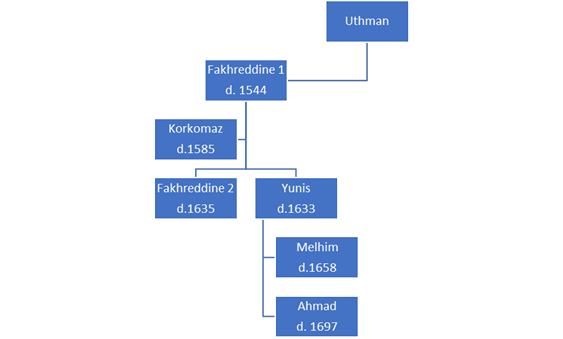

Figure 1: The Maan Genealogy as we know it

During the Maan dynasty reign, 3 Alameddine emirs succeeded to the paramount chieftainship. Historians don’t provide much details about their background.

Figure 2:During the Maan chieftainship, Sulayman Alameddine, Ali Alameddine and Musa Alameddine also figure in the list of Amirs who governed the Shuf

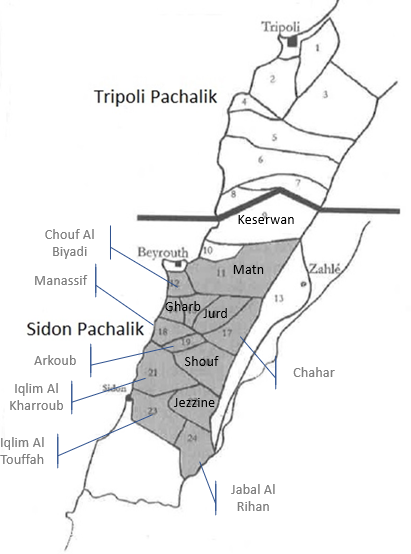

In the early 1590s an obscure chieftain of the Druze district of the Shuf (Chouf, Shouf, شوف ) was appointed multazim (tax farmer, ملتزم) of the whole Druze mountain (The Shuf along with the Gharb (غرب), Jurd (جرد) and Matn (متن), in the hinterland of Beirut) by the ottoman provincial governor of Damascus. The name of this chieftain was Fakhreddine ibn Korkomaz (فخر الدين ابن قرقماز), and he belonged to the family of Maans (معن), who had been hereditary chieftains of the Shuf at lease since 15th century. In time, Fakhreddine made use of favorable circumstances to extend his dominion over the whole of Mount Lebanon, and also over other parts of the syrian countryside. In 1633, however, the Ottomans turned against him and crushed him, and a mysterious figure called Ali Alameddine (علم الدين) was appointed to replace him in the paramount chieftains of the Druze mountain.

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Figure 3: Druze mountain at the time of Maan and Shihab

For over 3 decades, this man and his sons after him maintained themselves in power as paramount chieftains of the Druze, while the Maans were reduced to their original size as traditional chieftains of the Chouf. Finally, in 1667, Emir Ahmad Maan, a grandnephew of Fakhreddine, was appointed multazim of the Druze districts of Chouf, Gharb, Jurd and Matn, and the Maronite district of the Keserwan, and the Maanide hegemony over the southern Lebanon was thus re-established. When Ahmad Maan died without male progeny in 1697 he was succeeded in his Iltizam, and hence in the hegemony of the southern Lebanon, by the Shihabs – Sunnite chieftains of Wadi Al Taym, on the western slopes of Mount Hermon, who were descended from the Druze Maan in the female line. In 1710-1711 the Alameddines, in eclipse since 1667, re-emerged on the political scene to challenge the Shihab succession; their revolt, however, failed and they were massacred to extermination in Ain Dara battle. The Shihabs subsequently became the unchallenged masters of the southern Lebanon and remained so until their downfall in 1841.

Hence, the period 1591-1697 in the history of the southern Lebanon was a period of Maanid ascendency, except for the years between 1633 and 1667 when the Alameddines were in Power. For this Maanide period, as for the succeeding period of Shihab ascendency, information is not lacking, and the broad lines of the main political developments are known. What remains in a mystery is the rise of the Maans to power between 1517 and 1591 – a period in the history of the Druze mountain for which hardly any dependable information exists. What is even more of a mystery is the origin and unexplained appearance in 1633 of the Alameddines[4]: The one family in the Druze mountain with whose ambitions for paramount leadership the Maans, and after them the Shihab, had to contend.

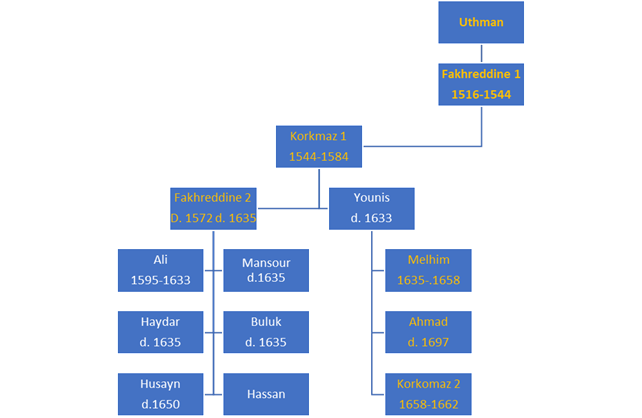

Figure 4: Relationshiop between the Maan family and its successor Shihab family. Historian Haydar Shihab is yellowed

In telling the story of the Maans before the rise of

Fakhreddine ibn Korkmaz, modern scholarship has depended mostly on two sources

dating back to no earlier than the 19th century, those being the

chronicle الغرار

الحسان في

تاريخ حوادث

الزمان by the Emir historian Haydar Shihab who (died

in 1835), and the compilation of genealogy and history entitled أخبار

الاعيان في

جبل لبنان (History of the nobles in

Mount Lebanon) by a former assistant and disciple of Haydar Shihab called

Tannous Shidiyac طنوس

الشدياق (died in 1861). According to these two

sources, a Maadnid emir called Fakhreddine ibn Ousman or Fakhreddine 1 (to be

distinguished from Fakhreddine ibn Korkmaz or Fakhreddine 2), was recognized as

the foremost Druze emir by the Ottoman Sultan Selim 1 in 1517, the year in

which the Ottoman conquest of Syria and Egypt was completed. Haydar Shihab (the

historian, son of Ahmad, son of Haydar Shihab, the Emir) relates to the story

as follows:

After the [ottoman] Sultan [Selim 1] had defeated the [Safawid] Shah [Ismail], he turned his forces to fight the ruler of Egypt. Thereupon the Mamluk Sultan of Egypt and Syria Al Ashraf Qansuh al-Ghuri advanced with his forces to the region of Aleppo, and the battle took place.. at Marj Dabiq … Khayr Bey was then viceroy in Aleppo, as was Janbirdi al-Ghazali in Damascus[5]… The Sultan al-Ashraf Qansuh ordered them to take command of the forces and advance to battle. Fakhreddine ibn Maan and the emirs of Jabal al-Shuf[6] were in the company of Khayr Bey and Al Ghazali. So Fakhr al-Din said to his men and companions: ”Let us stand aside to find who the victor would be so we would fight for him”. When the fighting broke out, Al-Ghazali and Khayr Bey fled over to join the forces of Sultan Selim along with the Syrian contingent in their company. Al-Ghuri was left alone with the Egyptian forces….[which were utterly routed… [Sultan Selim] thereupon entered Aleppo, took possession of Hama and Hims, and proceeded with his forces to Damascus…

Shihabi here proceeds to relate the conquest of Egypt by Selim 1, and the Sultan’s sojourn on his way back in Damascus (September 1517 to February 1518), then continues:

While in Damascus, [Selim] wrote to the emirs of Mount Lebanon granting them amnesty, Emir Fakhreddine, son of Emir Uthman ibn Maan, Emir Jamaleddine[7] al- Yamani, Emir Assaf al Turkumani[8], and other emirs in the countryside (Oumara Al Barr) appeared before him. But the Tanukhid[9] emirs were not present because they were allies of the Circassians… When the Emirs arrived before the Sultan in the company of Khayr Bey and al-Ghazali, Emir Fakhreddine advanced forward, kissed the ground, and made the following invocation…” O God perpetuate the term of him whom you have chosen for your rule, made successor (Khalifa) to your covenant, given power over our people and land, and armed with your sunna and fard, the champion of the luminous sharia, leader of the pure and victorious umma, our lord and benefactor the commander of the faithful, the just Imam, wise and munificent, who holds the rein of command, the Padishah, may God perpetuate his existence, keep him in continuous power, make his glory and splendor eternal in the world, maintain his good fortune to the Day of Resurrection, make him achieve his hopes and purposes, and provide him who rules with wisdom and diligence with favor and success! May God assist us in prayers that his rule continues in good fortune and be perpetuated in the happiest power facility! Amen”.

Having finished this invocation, Emir Fakhreddine came forward and kissed the sleeve of the [Sultan’s] garment. The Sultan inquired from Khayr Bey who he was; he told him he was an emir who lived in the countryside, ruling over villages and places in rugged mountains of the province (Iqta) of Damascus. Sultan Selim liked him because of his eloquence and courage; he was gracious to him and showed him favor, “Truly,” he said, “this man must be called lord of the countryside (Sultan al barr)”; and from that time Ibn Maan was called by this name… Other Emirs then asked for permission to enter into the presence of the Sultan, but they were told [that] since Fakhreddine had entered, no other need enter. Emir Fakhreddine was [then] assigned the Shuf, Emir Jamaleddine the Gharb, and Emir Assaf the Kisrouan and Jubayl.

Under the year 1544, Shihabi gives the following obituary notice for Fakhreddine ibn Uthman:

In this year Emir Fakhreddine ibn Uthman Maan died. He was a courageous man and ruled the land of Arabistan from the borders of Jaffa to Tripoli; all the territories there were under his command. He erected great buildings and fortresses, was untroubled in his rule, and was obeyed by the arabs. Upon his death he was succeeded by his son Korkmaz.

Further on in his chronicle, Shihabi points out, under the year 1572, that it was following the death of Fakhreddine ibn Uthman that the territorial domain of the Assaf in Kisrouan began to grow until it came to extend from Beirut in the south regions of Hims and Hama in the North, the suggestion being that the Assafs took advantage of a decline in Maanid power following the death of Fakhreddine ibn Uthman to expand their domain southwards and northwards.

As far as it can be determined, Shihabi was the first historian to speak of a Fakhreddine Maan who was confirmed in the chieftainship of the Shuf by Selim 1 in 1517, who came to rule the territory from Jaffa to Tripoli, and who died in 1544 to be succeeded by a son, Korkomaz, who was the father of the historical Fakhreddine ibn Korkomaz, or Fakhreddine 2. Tannous Shidyaq, in Akhbar Al Aayan (أخبار الاعيان في جبل لبنان) summarized what Shihabi had to say about the matter, establishing the maanid genealogy accordingly as follows:

Figure 5: Maan family tree as constructed by Haydar Shihab and Tannous Shidyac

It is said that the maanid

chief, Fakhreddine 1, made his submission to Selim at Damascus and received the

tiles of Sultan el Barr, but this may well be a later tradition reflecting the

unquestioned hegemony of his grandson. Actually, the only Fakhreddine Maan

known to have existed before the historical Fakhreddine ibn Korkomaz, was

Fakhreddine Uthman (not Fakhreddine ibn Uthman) who died in

August-September 1506. This Fakhreddine Uthman is mentioned by the

Druze historian Hamza ibn Sibat[10]

(d.1520), his contemporary, who describes him as “emir of the Ashwaf (plural of

Shuf), in the region of Sidon. The name of this emir is also found in an

inscription at the base of the minaret of mosque of Dayr al-Qamar: The

blessed place was built… by Al-Maqarr al Fakhri Emir Fakhreddine Uthman, son of

al Hajj Yunis ibn Maan… in 899 [A.D. 1493]

Like other dignitaries of the mamluk period, this Fakhreddine had two parts to his name: a laqab (pious sobriquet), Fakhreddine (pride of the faith), and an ism (given name) Uthman. By the time of Shihabi and Shidyak, the use of the laqab, and the distinction between ism and laqab types of name, had long been forgotten; a composite name like Fakhreddine Uthman was normally understood to mean Fakhreddine ibn (son of) Uthman (ism of son and ism of father, rather than laqab and ism of the same person), hence the error is Shihabi’s rendering the name. Actually, the father of Fakhreddine Uthman, as established by the Deir Al Qamar inscription, was Yunis (ism, with no laqab given).

Both men lived at the time of the great Druze reformer Jamaleddine Abdallah and Tanukhi (d.1479), commonly called Al-sayyid, who urged his followers to practice the orthodox Muslim rites. This probably explains why Yunis is described by Deir Al-Qamar inscription as al-Hajj (one who has gone on pilgrimage to Mecca), and why his son Fakhreddine Uthman had a mosque built in Deir Al-Qamar, the seat of the Maans. The description of Fakhreddine Uthman by the inscription as al-maqarr al-fakhri (the fakhrid seat) may indicate that the emir held a commission in the mamluk army; on the other hand, this honorific title could have been of no official significance, but merely a local emulation of the official usage.

Here the question arises: If Fakhreddine Uthman, as

has been established, was already dead (1506) ten years before the battle of

Mark Dabiq (1516), who actually was the Maanid chieftain of the Shuf at the

time of Ottoman conquest?

Writing in the late 17th century, the Maronite patriarch-historian Istfan al-Duwayhi[11] (1629-1704), who was personally acquainted with Emir Ahmad (1667-1697), the last was of the Maans, relates the following:

[After his conquest of Syria and Egypt, Sultan Selim] wrote to the emirs of the various regions (umara al-buldan), [granting them] amnesty and [summoning them to his] presence. Emir Korkomaz son of Emir Yunis ibn Maan, Emir Jamaleddine al-Yamani, Emir Assaf and others presented themselves before him, but not the Tanukhid emirs of the Gharb who were on the side of the Circassians. So [Selim] assigned the government of the Shuf to Emir Korkomaz, the Gharb to Emir Jamaleddine, and the Keserwan and the region of Jubayl to Emir Assaf…

This is the earliest account we have of the settlement of the affairs of the southern Lebanon, in 1517, by Selim 1; it has in it the main elements which Shihabi later used to construct his more fanciful narrative, except that the Maanid emir who was supposedly confirmed by the ottoman conqueror in the chieftainship of the Shuf is identified by Duwayhi as a Korkomaz ibn Yunis, not as Fakhreddine ibn Uthman. Ibn Sibat, who died only three years after the ottoman conquest, likewise speaks of a Krkomaz as chieftain of the Shuf at the time, but he does not identify him as the son of an emir Yunis, nor does he mention his confirmation in the chieftainship of the Shuf by Selim 1. On the other hand, Ibn Sibat does mention an Emir Yunis who could have been the father and predecessor of Emir Korkomaz. Under the year 1511-12 he related the following:

In this year Emir Yunis ibn Maan, emir of the Ashwaf,

died. The day of his burial was a great day because he was a young man of

reverence, power, and dignity.

Considering that the eldest sons of eldest sons, in traditional Islamic society, frequently carry the grandfather’s name, this Yunis Maan may safely be considered the son of Fakhreddine Uthman ibn al-Hajj Yunis and his successor, after 1516, in the chieftainship of Shuf. When he died in 1511 or 1512, he was apparently succeeded, in turn, by his son Korkomaz. According to Duwayhi, whose chronicle is he earliest and most reliable source of the history of the Lebanon regions in the 16th century, this Korkomaz was still chieftain of the Shuf in 1528.

In 1585-6 a Korkomaz died in the chieftainship of the Shuf, to be succeeded in time by his son, the so-called Fakhreddine 2. Duwayhi has nothing to say about the chieftainship of the Shuf between 1528 and 1585, but his text gives no reason to suppose that the Korkomaz of 1517 and 1528 and the Korkomaz who died in 1585 were not the same person. Accordingly, the genealogical table for the house of Maan must be reconstructed, at least tentatively as follows:

Figure 6: Sulayman Alameddine cogoverned with Korkomaz. He was probably a close cousin, maternal or paternal uncle

What apparently confused Shihabi in his attempt to reconstruct the history of Maanids in the early ottoman period was the unusually long tenure of the chieftainship of the Shuf by Korkomaz (approximately seventy-five years, from 1511-12 until 1585-6). Shihabi probably calculated that if Korkomaz had succeeded to the chieftainship of the Shuf at the age of, say, twenty. He would have sired his eldest son, Fakhreddine (born 1572), at the early age of eighty, and would have died fleeing before the Ottomans at the improbable age of ninety-five.

Putting aside the evidence of Duwayhi, Shihabi presumed that the Fakhreddine Uthman who died in 1506 was simply called Uthman, that this Uthman was succeeded by a son, Fakhreddine, who died in 1544 (a date which seems to have been chosen at random), and that this Fakhreddine, rather than the Yunis who died in 1511 or 1512, was the father of Korkomaz, and hence the grandfather of a namesake, Fakhreddine 2.

Actually, Korkomaz, if he was the son of Yunis, could not have been twenty when he succeeded his father in 1511-12. According to Ibn Sibat, Yunis died while still in his youth. Korkomaz must have succeeded him as a child. Until 1518 at least, he appears to have held the chieftainship of the Shuf in association with another Maanid emir called Alameddine Sulayman, who was probably an uncle or close cousin serving his guardian. That some sort of partnership existed between Korkomaz and his relative Alameddine Sulayman is clear from a story related, under the year 1518, by Ibn Sibat:

Emir Nasir al-Din Muhammad ibn al-Hanash, master of Sidon and the two Bekaa, revolted against… Selim… Janbirdi al-Ghazali thereupon advanced to the region of Sidon to seize him, but he escaped. [The tanukhid] emir Sharaf al-Din Yahya was accused of supporting [Ibn al-Hanash]. So when he came to meet Janbirdi [al-Ghazali] in the Sidon region he was seized along with Emir Zayn al-Din and the emirs Korkomaz and Alameddine Sulayman, sons of Maan, the emirs of the Shuf of Sidon. [The four prisoners] were taken to Sidon under close arrest, then sent in a ship, by sea, to Tyre, then …[transferred] to Safad, then after a time to the fortress of Damascus. When … Selim proceeded with his forces [back] to Analtolia (Bilad al-Rum), he took them with him to Aleppo while they were still [there] under arrest. After they were released, at a great expense to them.

Duwayhi was, as far as it can be determined, the first historian to mention the confirmation of Korkomaz in the chieftainship of the Shuf by Selim 1. He stated emphatically that while Korkomaz, Jamaleddine al-Yamani, Assaf and other regional chieftains readily responded to the summons of the Ottoman Sultan and proceeded to appear before his in Damascus, the Tanukhid emirs of the Gharb stayed behind because they were on the side of the Circassians. Curiously, Ibn Sibat, who was living (and probably writing) at the time of the Ottoman conquest, made no mention of the appearance of Korkomaz, Jamaleddine al-Yamani or Assaf before Selim 1 in Damascus in 1517. On the other hand, he distinctly mentioned two occasions on which the Tanukhid emir Sharaf al-Din Yahya went to Damascus to pau homage to the Ottoman conqueror:

[Sharaf al-Din Yahya] presented himself before … Selim… when… he took |Damascus [1516], kissed his hand, and served him; so [Selim], put his signature to [Yahya’s] mandshir (official document defining the tenure of an Iqta). Likewise, when [Selim] conquered Egypt and returned to Damascus [1517], [Yahya] again presented himself before him, kissed his hand, and offered him gifts which he accepted.

Duwayhi, on the whole, was a careful historian; he was, moreover, well acquainted with the history of Ibn Sibat, to which he made a number of references. It is therefore strange that he should have overlooked the fact that the Tanukhid Sharaf al-Din Yahya was the one chieftain of the southern Lebanon known to have met Selim 1 in Damascus by first-hand historical evidence.

Clearly, Duwayhi had preferred a traditional Maanid version of what happened in 1516-17 to the version if Ibn Sibat. At the time he was writing his history[12] the Maanids were still ruling the druze mountain; The Tanukhids, on the other hand, had been extinct for nearly half a century[13], and their version of what happened in 1516-17 had been forgotten, except for what had been preserved in the history of their servant Ibn Sibat. By relating the confirmation of Korkomaz in the chieftain of the Shuf by Selim 1 in 1517, Duwayhi was actually giving historical justification for the Maanid hegemony over the Druze mountain which had been re-established in his own time, in 1667, under his friend Ahmad Maan.

The first-hand evidence that Ibn Sibat establishes beyond doubt that the paramount chieftain of the Shuf was held in 1517 by two Maanid emirs, Korkomaz and Alameddine Sulayman, and not by a Fakhredine ibn Uthman, or Fakhreddine 1, as Shihabi and Shidyak led later historians to believe. The question however remains: If Korkomaz was the son of Yunis and the ancestor of the later Maanids (Fakhreddine, Yunis, Mulhim and Ahmad), who was the mysterious Alameddine Sulayman who was associated with him in the chieftainship of the Shuf at the time of the Ottoman conquest, and why does Duwayhi, despite his acquaintance with the history of Ibn Sibat, fail to mention him?

It is impossible to determine in what way Alameddine Sulayman was related to Korkomaz; he could have been a paternal or maternal uncle (in the former case, a brother to Younis), a cousin close enough to be associated with him in the leadership of the family, or even a brother, although this last possibility is remote.

The fact that Duwayhi does not mention him could mean one of tow things: either that Alameddine Sulayman was not a man of much consequence, so that he was, in time, forgotten; or else that he was a man of much consequence that the descendants of his associate Korkomaz preferred to have his memory suppressed. If the latter was the case, then not only the memory of Alameddine Sulayman, but the memory of whatever else was connected with him must have been suppressed by a historian like Duwayhi who was a friend and supporter of the ruling Maaninds, who were the descendants of Korkomaz.

Let us stop here to consider what gaps exist in Duwayhi’s chronicle where the history of the Shuf and the Maanid dynasty is concerned:

First, Duwayhi, as we have seen, overlooks the existence of Alameddine Sulayman as an associate of Korkomaz in the chieftainship of the Shuf in 1517.

Secondly, Duwayhi has nothing to say about the internal affairs of the Shuf between 1517 and 1584, except for a passing reference to Korkomaz as the emir of the region in 1528.

Thirdly, Duwayhi does not explain what happened in the Shuf between the death of Korkomaz in 1585 and the succession of his son Fakhreddine six years later; nor does he have anything to say about the career of Fakhreddine between 1591 and 1598.

Considering that Duwayhi, in his time, had close relations with the house of Maan, it is strange that he had so little to say about the history of the family in the sixteenth century- a past which was then still recent enough to be alive in the family and regional memory.

Duwayhi had a great deal to say about the career of Fakhreddine ibn Korkomaz after 1598. However, it is only when he comes to the year 1633, the year of Fakhreddin’s downfall, that he first mentions Ali Alameddine: the man who was apparently, the chief Druze opponent to Fakhreddine.

In that year, following the defeat of Fakhreddine and his capture by the Ottomans, Ali Alameddine, we are told, was appointed to replace him in the Shuf (By which Duwayhi probably meant the whole Druze mountain)[14]. Ali. Who headed the Yaman faction among the druzes, thereupon proceeded to massacre the Tanukhids of the Gharb who led the Qays faction that supported Fakhreddine[15].

[He] seized the supporters of the house of Maan, killed them and confiscated their property/ When he went to the village of Abay, in the Gharb, and was invited by the Tanukhid emirs to lunch in the serail which is below the village, he fell upon them killing Emir Yahya Al Aqil and the emirs Mahmud, Nasir al-Din, and Sayf al-Din. He then attacked the tower where their small children were and killed all three of them, leaving no child to succeed them.

Considering that Ali Alameddine became the leading chieftain of the Druze mountain in 1633, and that he proceeded forthwith to exterminate a whole family of chieftains, a mention of him under that year was unavoidable. But why is there no mention of this Ali before 1633?

Before attempting to answer this question, let us stop to consider what happened to Ali Alameddine and his descendants after 1633.

In that year, as we have seen, Ali replaced Fakhreddine in the paramount chieftainship of the Druze mountain; but he was soon to reckon, as paramount chieftain, with a stiff opposition from Fakhreddine nephew Mulhim, who now emerged as the leader of the Qays druzes. By 1636, Mulhim, it seems, had regained control of the Shuf; in 1650 he was appointed multazim of the Batrun district, in the northern Lebanon (Province of Tripoli); at the time of his death, in 1658, Mulhim was also multazim of the Sanjak of Safad, in the Galilee (province of Damascus), Meanwhile Ali Alameddine remained on the scene of the Druze mountain, apparently as paramount chieftain (at least in the Gharb, Jurd, and Matn) until his death in 1660- the year in which the southern Lebanon and Galilee were removed from the province of Damascus and organized as separate province of Sidon. Ali was succeeded by his tow sons: Muhammad and Mansur;

In 1662, his elder son, Muhammad, was recognized as paramount chieftain of the southern Lebanon in association with Qays chieftain called Shaykh Abu Alwan. Finally, in 1667, Ahmad, who had succeeded his father Mulhim as chieftain of the Shuf and a leader of the Qays Druzes, defeated the Alameddine and the Yaman Druzes outside Beirut and took over the rule of the Druze mountain and Keserwan. The Alameddine and their supporters were forced to flee to Damascus, where they settled in forced retirement. In 1693, Musa Alameddine, a son of Muhammad, paid a visit to Istanbul, where he secured permission from the Porte to overthrow Ahmad Maan and replace him in the paramount chieftainship of the Southern Lebanon. With Ottoman help, Musa Alameddine succeeded in evicting Ahmad Maan from his capital, Dayr Al Kamar, and establishing himself in his place; before long, however, he lost heart and fled to Damascus , and Ahmad Maan returned to his emirate .

In 1698, the year following the death of Ahmad Maan, Musa Alameddine took a second trip to Istanbul, where he presented himself this time as a candidate to replace Bachir Shehab I in the Druze emirate, but without success. In 1710-1711, when the Yaman Druzes of the Southern Lebanon rose in revolt against Bashir Shihab’s successor Haydar, Musa Alameddine led his kinsmen and supported back to the southern Lebanon in a last attempt to reclaim the paramount Druze chieftainship for his family. Musa, however, was defeated and killed in battle, and his family was subsequently exterminated (Ain Dara battle).

From this brief review of the history of the Alameddine between 1633 and 1711, it is clear that they were a family which had some special claim to the chieftainship of the Shuf, and hence to the paramount chieftainship of the Druze mountain that went with it. No other Druze chieftains, between 1633 and 1697, rose to dispute the leadership of the Maans. In 1697, because no legitimate or acceptable successor to the Maans was found among the Druze chieftains of the southern Lebanon, these chieftains agreed to the succession of the Shihabs, who were sunnites from Wadi al-Taym related to the Maans in the female line, and hence having a claim, albeit arguable, to the succession. When a Druze family appeared, in 1698 then in 1710-11, to challenge the succession of the Shihabs, it was again the Alameddine. Could it have been that these Alameddines, who presented themselves so persistently as claimants to the Druze emirate between 1633 and 1711, were no other than the descendants of Maanid emir Alameddine Sulayman, the associate of Kormokaz in the chieftainship of the Shuf at the time of the Ottoman conquest? In other words, is it possible that there were, during the 16th and 17th centuries, two branches to the Maan family, a house of Korkomaz and a rival house of Alameddine?

Writing at the time of Ahmad Maan (d 1697), who was a friend and protector to the Maronites, Duwayhi (August 2, 1630 – May 3, 1704), as Maronite patriarch, was hardly in a position to advance the historical claims of a Maanid house of Alameddine to the emirate, had such a rival Maanid house existed. This may well be the explanation of why Duwayhi omits the mention of the Maanid emir Alameddine Sulayman in 1517, why he ignores the developments in the Shuf until Fakhreddine, son of Korkomaz, was firmly established in power in 1598, and why he has nothing to say about the career of Ali Alameddine, who was obviously a Druze leader of great importance, until this Ali actually replaced Fakhreddine in the paramount chieftainship of the southern Lebanon in 1633.

Like Duawyhi, Ahmad ibn Muhammad al-Khalidi of Safad, who served Fakhreddine as secretary and wrote a history of his rule from 1612 until 1623, records in detail the developments of these years and gives abundant information about the opposition which Fakhreddine faced in the Druze mountain, but never once does mention Ali Alameddine, or any other Alameddine, although the Alameddines must certainly have been politically active at the time. Could it have been that Khalidi under Emir Fakhreddine, and Duwayhi under Emir Ahmad, were each party to a conspiracy of silence ordained by the ruling house of Korkomaz against their Alameddine cousins and rivals?

If the Korkomaz of 1517, as Duwayhi says, was the son of Younis, and therefore a mere child at the time of the Ottoman conquest, then his fellow chieftain Alameddine Sulayman, as already suggested, was probably an older relative -perhaps an uncle – who was associated with him in the chieftainship of the Shouf because of his minority. A quarrel between the two Maan emirs could have broken out once the young Korkomaz had come of age. Such a quarrel may explain why Korkomaz, in 1528, was apparently established in the village of Barouk[16], and not in Deir Al-Kamar, where his predecessors appear to have resided. One might presume that Alameddine Sulayman had remained behind Deir Al-Kamar, unwilling to relinquish his association in the chieftainship, and forcing his younger associate to move elsewhere. Moreover, since Korkomaz was supported by the Qays faction among the Druzes, and ultimately married into the Tannukhid family, who were the leading Qays chieftains of the Gharb, it was only natural that Alameddine Sulayman, or his sons and successors after him, should turned for support to the Yaman faction, establishing themselves as its leaders. It was possibly Alameddine intrigues that led to the invasion of the Shouf by the Ottomans in 1585, and the death of Korkomaz in fight[17]. Whatever the case, Korkomaz, in 1585, was not succeeded in the Shouf by his elder son Fakhreddine until 1591. Duwayhi’s account of what happened in the intervening years seems to be studiedly brief and vague:

In the circumstances [?] Emir Sayfeddine Tannukh sent for his sister’s children, Emir Fakhreddine and his brother Emir Younis, and brought them over to the Shouf [to keep them] with him. When the six years were over, Emir Sayfeddine returned to Abay, in the Gharb, and appointed Emir Fakhreddine to govern the Shouf.

Considering that Fakhreddine and Younis were maanids of the Shouf, and that their maternal uncle, Sayfeddine Tannoukh, was a chieftain of the Gharb, the likelihood was that Sayfeddine had his two nephews “brought over”, to stay with him in the Gharb, not in the Shouf because the Shouf had meamwhile fallen under Alameddine Control. Duwayhi, however, may not have wished to admit this, hence his lame explanation of what happened during the “six years”.

Any admission by Duwayhi of the existence of the Alameddine as rival claimants to the chieftainship of the Shouf before 1633 would have strengthened the claims of the house of Alameddine against those of the house of Korkomaz.

To promote the image of Ahmad Maan, after 1667, as the legitimate successor to the chieftainship of the Shouf and the hegemony of the Druze mountain, it was necessary to make Ali Alameddine in 1633, and his sons Muhamad and Mansour after 1660, appear as much as possible as usurpers. By maintaining a strict silence about the internal affairs of the Shouf between 1517 and 1591, and by introducing Sayfeddine Tannoukh as the guardian of the Maanide interests there between 1585 and 1591, Duwayhi may have been contributing to guard a family secret of the house of Korkomaz.

A contemporary description of Ahmad Maan by the English traveler Henry Maundrell, who travelled through Lebanon in the 1697, depicts his as just the sort of man to have had a skeleton in his closet: Achmet, grandson to Faccardine; an old man, and one who keeps up the custom of his ancestors, of turning day into night: an hereditary practice in his family, proceeding from a traditional persuasion amongst them, that princes can never sleep securely but by day, when men’s actions and designs are best observed by their guards, and if need be, most easily prevented; but that in the night it concerns them to be always vigilant, lest the darkness, aided by their sleeping, should give traitors both opportunity and encouragement to assault their persons, and by a dagger or pistol, to make them continue their sleep longer than intended when they lay down.

If we accept the hypothesis that there were two branches of the Maanid family, a house of Korkomaz and a house of Alameddine, then the Maanid male would have died out with the death of Emir Ahmad in 1697, but would have survived in the house of Alameddine which was established in the exile in the outskirts of Damascus. The Alameddine claim to the succession, in that case, would have been arbitrarily passed over in favour of Bashir Shihab then of Haydar Shihab, who were descended from the Maanid house of Korkomaz in the female line, and who were neither Druzes nor natives of the southern Lebanon.

The claim of the Alameddine, especially if they were Maanid, would have been the stronger one to the succession. When the Alameddine, in 1698 and in 1710-11, returned to the southern Lebanon to attempt the overthrow of the Shihabs, the justification of their return might well have been the reclamation of the Druze emirate from the Sunnite and alien Shihab line for their own more legitimate Maanid line. As it was, however, the Alameddine were defeated and exterminated by the Shihabs, and the basis of their claim to the emirate, whatever it may have been, was again suppressed, or merely forgotten. The conspiracy of silence against the Alameddine, so clearly observable under the Maans, continued under the Shihabs; the skeleton in the closet remained, through the closet had changed hands.[18]

With so much history suppressed to accommodate the political history interests of the Maanid house or Korkomaz and its Shihab successors, it is no wonder that later historians had to resort to invention. Hence Shihab and after him Shidyaq, puzzled by the prolonged rule of Korkomaz Maan in the Shuf, introduced for him as father and predecessor a Fakhreddine 1 who died in 1544. The son of Korkomaz, Fakhreddine, consequently became Fakhreddine 2. To make the Maanid hegemony over the Druze mountain, which was a personal achievement of Fakhreddine ibn Korkomaz, historically more prestigious, Shihabi had the legendary Fakhreddine 1 go in 1517 to meet Selim 1 in Damascus and receive from him the title of Sultan al-Barr, thereupon to become the ruler of the whole stretch of countryside from the border of Jaffa to Tripoli. In the scheme devised by Shihabi and followed by Shidyak, the paramountcy of the Maanid, established in the southern Lebanon in the very year of the Ottoman conquest by no less a person than Selim 1 himself, has passed in orderly succession from Fakhreddine 1 to Korkomaz, from Korkomaz to Fakhreddine 2, from Fakhreddine 2 to his nephew Melhim, from Melhim to Ahmad, and from Ahmad to the Shihabs. In this tidy scheme of succession, the Alameddine have no place; they merely feature, on and off, as mysterious and sinister usurpers who misgoverned the Druze mountain when the Maanids and Shihabs were suffering reverses of fortune, and who were ultimately of no consequence. Like other losers in history, they were only remembered after 1711 for the evil that lived after them: had they succeeded they might have been better and more charitably remembered.